Emiliano Rossi ID

Médico cardiólogo. Departamento de Investigación. Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires.

Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam 2021;51(4):372-374

Recibido: 05/09/2021 / Aceptado: 29/10/2021 / Publicado en www.actagastro.org el 13/12/2021 / https://doi.org/10.52787/FYYW6593

El acto médico se basa en la toma de decisiones en condiciones de incertidumbre. Todo lo que hagamos para reducirla aumenta nuestra probabilidad de éxito. Para ello, es fundamental hacer una adecuada interpretación de los resultados de los test diagnósticos.

Vamos a recordar las principales definiciones que hacen a la precisión de un test diagnóstico. Las dos medidas básicas son su sensibilidad (S) y especificidad (E). La S es la probabilidad de tener un resultado positivo del test en pacientes que tienen la enfermedad. La E es la probabilidad de tener un resultado negativo en pacientes que no tienen la enfermedad. Al hablar de enfermedad nos estamos refiriendo a la condición que el test sea capaz de detectar.1

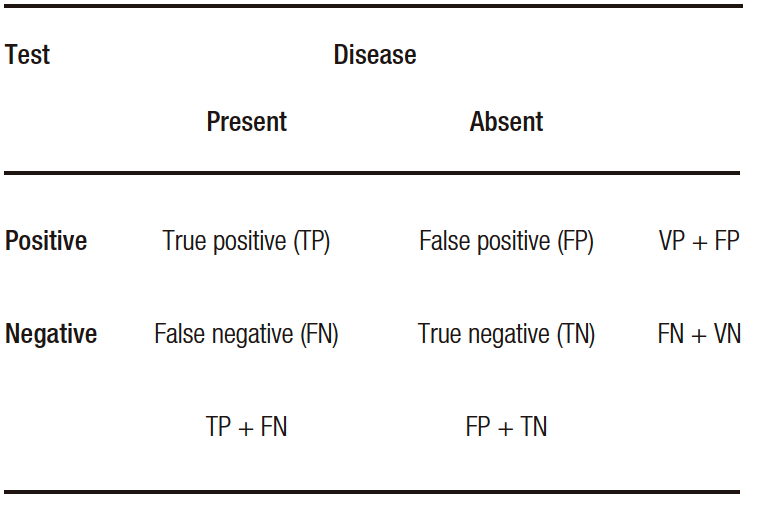

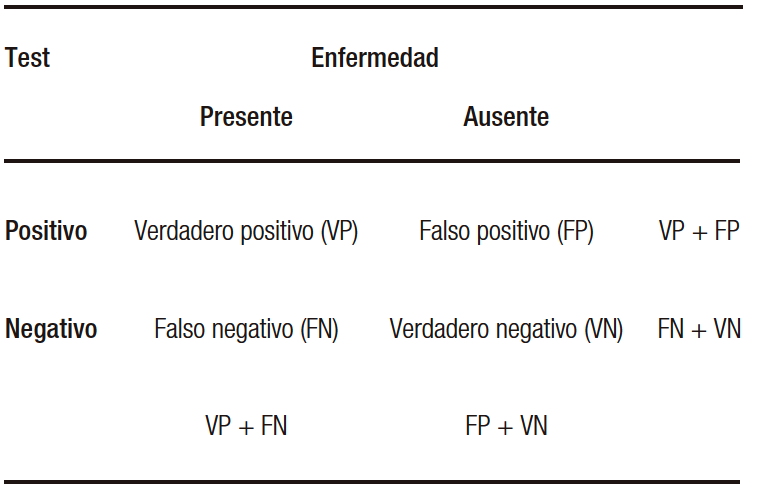

Al realizar un test diagnóstico vamos a encontrar cuatro situaciones posibles. Los verdaderos positivos (VP) son aquellos pacientes con la enfermedad en quienes el test es positivo. Los verdaderos negativos (VN) son aquellos pacientes sin la enfermedad en quienes el test es negativo. Los falsos negativos (FN) son aquellos con la enfermedad en quienes el test es falsamente negativo. Los falsos positivos (FP) son aquellos sin la enfermedad en quienes el test es falsamente positivo. Entonces, podemos definir la S como la probabilidad de encontrar un VP entre los pacientes que tienen la enfermedad (VP/VP+FP) y la E como la probabilidad de tener un VN entre aquellos que no tienen la enfermedad (VN/VN+FP) (Tabla 1).1

Tabla 1. Precisión diagnóstica de un test

Para interpretar los resultados de un test diagnóstico es necesario responder las siguientes preguntas: ¿cuál es la probabilidad de que un paciente tenga la enfermedad si tiene un resultado positivo? y ¿cuál es la probabilidad de que un paciente no tenga la enfermedad si tiene un resultado negativo? Las respuestas a estas preguntas son el valor predictivo positivo (VPP) y el negativo (VPN), respectivamente.1

Resumiendo, para la interpretación de los resultados deben considerarse, además del rendimiento diagnóstico del test, el contexto clínico y la prevalencia de la enfermedad en la población estudiada.

Trataremos de incorporar estos conceptos aplicándolos a un problema de relevancia epidemiológica como la pandemia de covid-19. Es sabido que la detección precoz y el aislamiento de los pacientes infectados con SARS-CoV2 es uno de los pilares fundamentales para disminuir la propagación de la enfermedad.

Desde la primera secuenciación genética del SARS-CoV-2 se han desarrollado test de amplificación de ácidos nucleicos (RT-PCR) para la detección del virus en varios tipos de muestras clínicas, frecuentemente hisopado nasofaríngeo y orofaríngeo. La Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS) continúa recomendando actualmente el diagnóstico de covid-19 mediante pruebas moleculares que detectan el ARN del virus SARS-CoV-2.2

La precisión diagnóstica de la RT-PCR para la detección de la infección activa por SARS-CoV-2 se ha reportado con una sensibilidad del 81,5-92,2% y una especificidad del 87-100%. Si bien son pruebas muy específicas que pueden detectar niveles bajos de ARN viral, su sensibilidad en el contexto clínico depende del tipo y la calidad de la muestra obtenida, la duración de la enfermedad al momento de la evaluación y las características del test. Es importante recordar que cuando la probabilidad pretest es alta, un resultado positivo debe considerarse como confirmatorio. En cambio, uno negativo debe hacer considerarnos el retesteo (debido a que los test no son 100% sensibles).2-4

Consideremos un primer escenario de un paciente con síntomas compatibles con covid-19, perteneciente a una población que tiene una baja prevalencia de infección por SARS-CoV2, en el que estimamos una probabilidad pretest de enfermedad del 20% y al que le realizamos un test RT-PCR que posee, según el fabricante, una S 90% y una E 95%. Responderemos nuestra primera pregunta: ¿cuál es la probabilidad de que un paciente tenga la enfermedad si tiene un resultado positivo? VPP= VP/(VP+FP)= 90/(90+5)= 0,95 o 95%. Ahora responderemos nuestra segunda pregunta: ¿cuál es la probabilidad de que un paciente no tenga la enfermedad si tiene un resultado negativo? Para esto calcularemos el VPN. VPN= VN/(VN+FN)= 95/(95+10)= 0,9 o 90%.

Sin embargo, es más útil calcular la probabilidad postest (P) positiva y negativa a partir del teorema de Bayes, el cual permite estimarlas a partir de la S y E del test y de la probabilidad pretest de la enfermedad. Al incorporar la probabilidad de tener la enfermedad antes de realizar el test se tiene en cuenta el contexto clínico en el que este se realiza. La probabilidad pretest (p) va a depender, como mencionamos, de los antecedentes del paciente, las manifestaciones clínicas y la prevalencia de la enfermedad en la población.

Aplicaremos estos conceptos a nuestro primer ejemplo.

La probabilidad postest (P) positivo es la probabilidad de tener la enfermedad dado un test positivo.

P (enfermedad | test+)= [S x p] / [S x p + (1 – E) x (1 – p)]= [0,9 x 0,2] / [0,9 x 0,2 + (1 – 0,95) x (1 – 0,2)]= 0,81 o 81%

La probabilidad postest negativo es la probabilidad de no tener la enfermedad dado un test negativo.

P (no enfermedad | test-) = [E x (1 – p)] / [E x (1 – p) + (1 – S) x p]= [0.95 x (1 – 0,2)] / [0.95 x (1 – 0,2) + (1 – 0,9) x 0,2]= 0,97 o 97%.

Veremos un segundo escenario de un paciente con síntomas compatibles con covid-19, al que le realizamos el mismo test RT-PCR (S 90% y una E 95%), aunque, esta vez el paciente proviene de una población con alta prevalencia de SARS-CoV2, en la que estimamos una probabilidad pretest del 50%. La estimación del VPP y VPN teóricos será la misma que en el caso anterior, pero no así la probabilidad postest basada en la probabilidad pretest.

P (enfermedad | test+) = [S x p] / [S x p + (1-E) x (1 – p)] = [0,9 x 0,5] / [0,9 x 0,5 + (1 – 0,95) x (1 – 0,5] = 0,95 o 95%

P (no enfermedad | test-) = [E x (1 – p)] / [E x (1 – p) + (1 – S) x p]= [0.95 x (1 – 0,5)] / [0.95 x (1 – 0,5) + (1-0,9) x 0,5]= 0,90 o 90%.

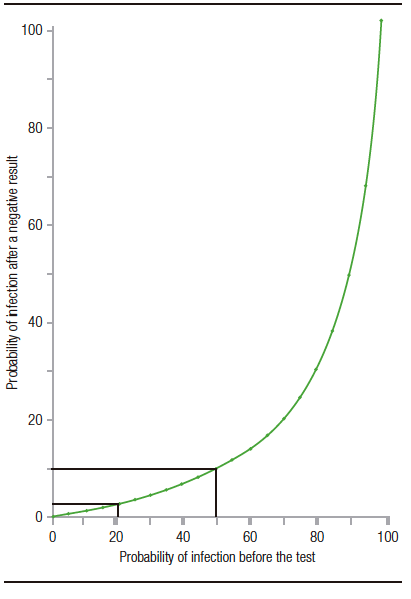

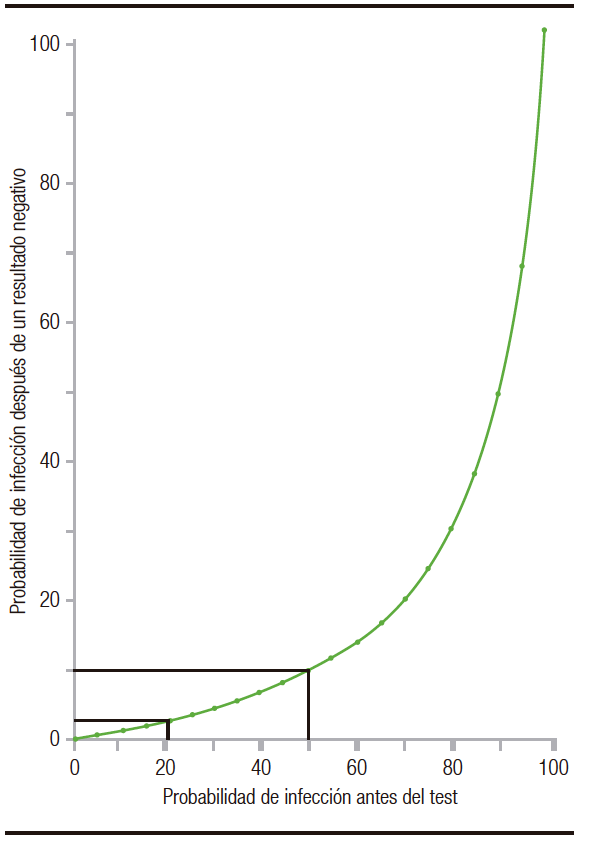

Observamos que a medida que aumenta la prevalencia pretest, disminuye la probabilidad de no tener la enfermedad dado un test negativo (aun manteniendo constantes la S y E) (Figura 1).5 En nuestro ejemplo pasamos de una P (no enfermedad | test-) de 97% al 90%. Es por ello que en un contexto epidemiológico de alta circulación viral un resultado negativo de un test, por más que este posea alta S y E, no descarta la infección por SARS-CoV-2.

Figura 1. Probabilidad de infección por SARS-CoV2 después de tener un resultado negativo, frente a distintas probabilidades pretest (para un test con una sensibilidad del 90% y una especificidad del 95%)

Aviso de derechos de autor

© 2021 Acta Gastroenterológica Latinoamericana. Este es un artículo de acceso abierto publicado bajo los términos de la Licencia Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0), la cual permite el uso, la distribución y la reproducción de forma no comercial, siempre que se cite al autor y la fuente original.

© 2021 Acta Gastroenterológica Latinoamericana. Este es un artículo de acceso abierto publicado bajo los términos de la Licencia Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0), la cual permite el uso, la distribución y la reproducción de forma no comercial, siempre que se cite al autor y la fuente original.

Cite este artículo como: Emiliano Rossi. Test diagnósticos: ¿Nos basta con considerar su sensibilidad y especificidad? Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam. 2021;51(4):372-4 https://doi.org/10.52787/FYYW6593

Referencias

- Weinstein S, Obuchowski NA, Lieber ML. Clinical evaluation of diagnostic tests. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(1):14-9. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.1.01840014. PMID: 15615943.

- Consenso sobre el uso de pruebas diagnósticas para SARS COV-2, versión 2 (actualizada al 03/05/2021). Ministerio de Salud de la Nación, Argentina.

- Kanji, J.N., Zelyas, N., MacDonald, C. et al. False negative rate of COVID-19 PCR testing: a discordant testing analysis.Virol J 18, 13 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-021-01489-0

- Sethuraman N, Jeremiah SS, Ryo A. Interpreting Diagnostic Tests for SARS-CoV-2. JAMA. 2020;323(22):2249-51. doi:10.1001/ jama.2020.8259

- Woloshin S, Patel N, Kesselheim AS. False Negative Tests for SARS-CoV-2 Infection – Challenges and Implications. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(6):e38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2015897. Epub 2020 Jun 5. PMID: 32502334.

Correspondencia: Emiliano Rossi

Correo electrónico: emiliano.rossi@hospitalitaliano.org.ar

Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam 2021;51(4):372-374

Diagnostic Test: Is It Enough to Consider Sensitivity and Specificity?

Emiliano Rossi ID

Cardiologist. Department of Investigation. Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires. Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam 2021;51(4):375-377

Received: 05/09/2021 / Accepted: 29/10/2021 / Published online: 13/12/2021 / https://doi.org/10.52787/FYYW6593

The medical act is based on making decisions under conditions of uncertainty. Everything we do to reduce it increases our probability of success. For this, it is essential to make an adequate interpretation of the results of the diagnostic tests.

We are going to remember the main definitions that establish the precision of a diagnostic test. The two basic measures are sensitivity (S) and specificity (E). Stands for is the probability of having a positive test, result in patients who have the disease and E is the probability of having a negative result in patients who do not have the disease. When we speak of disease we are referring to the condition that the test is capable of detecting.1

When performing a diagnostic test, we will find four possible situations. The true positives (TP) are those patients with the disease in whom the test is positive and the true negatives (TN) are those patients without the disease in whom the test is negative. False negatives (FN) are those with the disease in whom the test is falsely negative, whereas false positives (FP) are those without the disease in whom the test is false positive. Then, we can define S as the probability of finding a TP among patients who have the disease (TP + FN) and E as the probability of having a TN among those without it (TN + FP) (Table 1).1

Table 1. Diagnostic accuracy of a test

To interpret the results of a diagnostic test, it is necessary to answer the following questions: what is the probability that a patient has the disease if he has a positive result? and, what is the probability that a patient does not have the disease if he has a negative result? The answers to these questions are the positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV), respectively.1

In summary, the clinical context and the prevalence of the disease in the population studied, in addition to the diagnostic performance of the test, must be considered for the interpretation of the results.

We will try to incorporate these concepts by applying them to a problem of epidemiological relevance such as the COVID-19 pandemic. It is known that the early detection and isolation of patients infected with SARS-CoV2 is one of the fundamental pillars to reduce the spread of this disease.

Since the first genetic sequencing of SARS-CoV-2, nucleic acid amplification tests (RT-PCR) have been developed to detect the virus in various types of clinical samples, frequently nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs. The World Health Organization (WHO) currently continues to recommend the diagnosis of COVID-19 using molecular tests that detect the RNA of the SARS-CoV-2.2

The diagnostic accuracy of RT-PCR for the detection of active SARS-CoV-2 infection has been reported with a sensitivity of 81.5-92.2% and a specificity of 87-100%. Although they are very specific tests that can detect low levels of viral RNA, their sensitivity in the clinical context depends on the type and quality of the sample obtained, the duration of the disease at the time of evaluation, and the characteristics of the test. When the pre-test probability is high, a positive result should be considered confirmatory. Instead, a negative one should make us consider retesting (because the tests are not 100% sensitive).2-4

Let us consider a first scenario of a patient with symptoms compatible with COVID-19, belonging to a population that has a low prevalence of SARS-CoV2 infection, with an estimate pre-test probability of disease of 20% and we perform an RT-PCR test that has, according to the manufacturer, an S 90% and an E 95%. First, we will answer our first question: what is the probability that a patient will have the disease if the test is positive? PPV = TP / (TP + FP) = 90 / (90 + 5) = 0.95 or 95%. Now, we will answer our second question: what is the probability that a patient does not have the disease if he has a negative result? For this, we will calculate the NPV. NPV = TN / (TN + FN) = 95 / (95 + 10) = 0.9 or 90%.

However, it is more useful to calculate the positive and negative post-test probability (P) from Bayes’ theorem, which allows estimating them from the S and E of the test and the pre-test probability of the disease. By incorporating the probability of having the disease before performing the test, the clinical context in which it is performed is taken into account. The pre-test probability (p) will depend, as mentioned, on the patient’s history, clinical manifestations and the prevalence of the disease in the population.

We will apply these concepts to our first example.

The positive post-test probability (P) is the probability of having the disease given a positive test.

P (disease | test+) = [S xp] / [S xp + (1 – E) x (1 – p)] = [0.9 x 0.2] / [0.9 x 0.2 + (1 – 0.95) x (1 – 0.2)] = 0.81 or 81%

The negative post-test probability is the probability of not having the disease given a negative test.

P (no disease | test-) = [E x (1 – p)] / [E x (1 – p) + (1 – S) xp] = [0.95 x (1 – 0.2)] / [0.95 x (1 – 0.2) + (1 – 0.9) x 0.2] = 0.97 or 97%.

We will see a second scenario of a patient with symptoms compatible with COVID-19, to whom we perform the same RT-PCR test (S 90% and E 95%); although, this time the patient comes from a population with a high prevalence of SARS-CoV2 in which we estimate a pre-test probability of 50%. The estimation of the theoretical PPV and NPV will be the same as in the previous case, but not the post-test probability based on the pre-test probability.

P (disease | test+) = [S xp] / [S xp + (1-E) x (1 – p)] = [0.9 x 0.5] / [0.9 x 0.5 + (1 – 0.95) x (1 – 0.5] = 0.95 or 95%

P (no disease | test-) = [E x (1 – p)] / [E x (1 – p) + (1 – S) xp] = [0.95 x (1 – 0.5)] / [0.95 x (1 – 0.5) + (1-0.9) x 0.5] = 0.90 or 90%.

We observe that, as the pre-test prevalence increases, the probability of not having the disease decreases given a negative test (even keeping the S and E constant) (Fig. 1).5 In our example, we go from a P (no disease | test-) from 97% to 90%. For this reason, in an epidemiological context of high viral circulation, a negative test result, even if it has high S and E, does not rule out SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Figure 1. Probability of SARS-CoV2 infection after a negative result, compared to different pre-test probabilities (for a test with a sensitivity of 90% and a specificity of 95%)

Copyright

© 2021 Acta Gastroenterológica latinoamericana. This is an open-access article released under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license, which allows non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction, provided the original author and source are acknowledged.

© 2021 Acta Gastroenterológica latinoamericana. This is an open-access article released under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license, which allows non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction, provided the original author and source are acknowledged.

Cite this article as: Emiliano Rossi. Diagnostic Test: Is It Enough to Consider Sensitivity and Specificity? Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam. 2021;51(4):375-377. https://doi.org/10.52787/FYYW6593

References

- Weinstein S, Obuchowski NA, Lieber ML. Clinical evaluation of diagnostic tests. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005 Jan;184(1):14-9. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.1.01840014. PMID: 15615943.

- Consenso sobre el uso de pruebas diagnósticas para SARS COV-2, versión 2 (actualizada al 03/05/2021). Ministerio de Salud de la Nación, Argentina.

- Kanji, J.N., Zelyas, N., MacDonald, C. et al. False negative rate of COVID-19 PCR testing: a discordant testing analysis. Virol J 18, 13 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-021-01489-0

- Sethuraman N, Jeremiah SS, Ryo A. Interpreting Diagnostic Tests for SARS-CoV-2. JAMA.2020;323(22):2249–2251. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.8259

- Woloshin S, Patel N, Kesselheim AS. False Negative Tests for SARS-CoV-2 Infection – Challenges and Implications. N Engl J Med. 2020 Aug 6;383(6):e38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2015897. Epub 2020 Jun 5. PMID: 32502334.

Correspondence: Emiliano Rossi

Email: emiliano.rossi@hospitalitaliano.org.ar

Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam 2021;51(4):375-377

Revista ACTA Órgano Oficial de SAGE

Revista ACTA Órgano Oficial de SAGE