Carlos Saul ID· Guilherme Pereira Lima ID· Abdon Pacurucu Merchan ID· Julio C Pereira-Lima ID

Hospital Universitario Canoas, Brazil.

Canoas, Brazil.

Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam 2023;53(2):164-168

Received: 06/03/2023 / Accepted: 15/06/2023 / Published online: 30/06/2023 /

https://doi.org/ 10.52787/agl.v53i2.307

Summary

Introduction. Endoscopic capsule is central to the study of the small bowel. Retention is its main complication. Objective. To analyze the frequency and risk factors associated with capsule retention. Methods. 244 consecutive examinations were analyzed. The event was defined as “definitive retention” if the capsule remained in the small bowel for 3 weeks after the procedure, and as “temporary retention” if the capsule remained in the small bowel at the end of the procedure but was eliminated spontaneously in the following days. Risk factors associated with retention were inflammatory small bowel strictures, tumours and large diverticula. Result. Of 244 procedures, lesions were found in 164 (67.2%), 130 of which were in the small bowel. There were 5 and 2 patients with definitive and temporary retention, respectively. Forty-four cases had risk factors. In 7 (15.9%) there was retention of the endoscopic capsule, with definitive retention in 5 cases. The 2 cases of temporary retention occurred in Meckel’s diverticulum and in peptic ulcer scar. The 5 cases of definitive retention occurred in 2 patients with Crohn’s disease, 2 patients with stenosis related with anti-inflammatory drugs use and 1 patient with actinic stenosis. None of the 11 cases of small bowel neoplasia had capsule retention. Conclusions. There was no endoscopic capsule retention in patients without risk factors. Definitive retention was observed in approximately one-tenth of all patients with small bowel risk factors. Recognition of risk factors and their identification prior to the procedure is of utmost importance, especially in patients with suspected inflammatory strictures.

Keywords. Endoscopic capsule, retention, small-bowel, endoscopy.

Retención de cápsula endoscópica: frecuencia, causas y análisis de factores de riesgo en 244 procedimientos consecutivos

Resumen

Introducción. La cápsula endoscópica es fundamental en la investigación del intestino delgado. La retención es su principal complicación. Objetivo. Analizar la frecuencia y los factores de riesgo relacionados con la retención de cápsula. Métodos. Fueron analizados 244 exámenes consecutivos. El evento fue definido como “retención definitiva” si la cápsula permanecía en el intestino delgado durante 3 semanas después del procedimiento y como “retención temporal” cuando al finalizar el procedimiento la cápsula aún se mantenía dentro del intestino delgado, pero era eliminada en los próximos días de manera espontánea. Los factores de riesgo relacionados con la retención fueron estenosis inflamatorias de intestino delgado, tumores y divertículos de gran tamaño. Resultados. De 244 exámenes, se encontraron lesiones en 164 (67,2%) y, de éstas, 130 en el intestino delgado. Presentaron retención definitiva y temporal 5 y 2 pacientes respectivamente. Tenían factores de riesgo 44 casos. En 7 (15,9%) de ellos, hubo retención de la cápsula endoscópica, siendo retenciones definitivas en 5 casos. Los 2 casos de retención temporal se presentaron en el divertículo de Meckel y en la cicatriz de una úlcera péptica. Las 5 retenciones definitivas ocurrieron en 2 pacientes con Enfermedad de Crohn, 2 pacientes con estenosis por uso de antiinflamatorios y 1 paciente con estenosis actínica. En ninguno de los 11 casos de neoplasia de intestino delgado hubo retención de la cápsula. Conclusión. No hubo retención de capsula endoscópica en pacientes sin factores de riesgo. Se observó retención definitiva en aproximadamente una décima parte de todos los pacientes con factores de riesgo en intestino delgado. El reconocimiento de los factores de riesgo y su identificación antes del procedimiento son de suma importancia, especialmente en pacientes con sospecha de estenosis inflamatoria.

Palabras claves. Cápsula endoscópica, retención, intestino delgado, endoscopía.

Abreviaturas

EC: Endoscopic capsule.

SB: Small bowel.

OGIB: Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding.

RF: Risk factors.

NSAIDs: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

CD: Chron’s disease.

Introduction

Endoscopic capsule (EC) is an important tool for the study of the small bowel (SB). EC allows physiological and non-invasive visualization of the SB.1-3 According to an ASGE guideline, “wireless capsule endoscopy has become the first-line test for visualization of the SB mucosa and its lesions, with an accuracy of 80%».4-6 The main complication is capsule retention, which occurs in 2 to 3% of the procedures and usually indicates a clinical problem.7 There are several indications for EC, including obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB),3, 8-11 patients with suspected or established Crohn’s disease,12 abdominal pain and chronic diarrhea.3, 13-19 Impaction in the cricopharynx,20 Zenker’s diverticulum21 or Meckel’s diverticulum22 have been described and are very rare causes of EC retention.4 In previous studies SB cancer and SB strictures were associated with EC retention and even considered a contraindication to the procedure.4, 23-25 The goal of our study is to evaluate the frequency of EC retention as well as its risk factors in a consecutive series of 244 EC procedures.

Material and Methods

Between 2007 and 2016, we analyzed 244 consecutive SBECs (GIVEN/Medtronic, models M2A and PillCam SB, SB 2 and SB 3). All patients had previously undergone upper and lower endoscopy, with no clinically significant findings in these segments. Indications for the use of EC were OGIB, anemia, search for polyps in patients with polyposis syndromes, investigation of diarrhea or neoplasms, abdominal pain, evaluation in patients with celiac disease and suspected or known cases of Crohn’s disease. Risk Factors (RF) were considered: Inflammatory narrowing of the small bowel (Crohn’s disease, use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), previous small bowel radiation, ulcers or lesions in Meckel’s diverticulum and other enteritis), SB tumors, scars (stenosis in treated Crohn’s disease, in surgical anastomosis, scar retraction of duodenal ulcer), and diverticula. The EC was considered to be definitively retained if it was still in the SB at three weeks after the procedure as shown by radiographs or had been surgically removed. Temporary retention was considered if the CE was still in the SB at the end of the study, but passed spontaneously in the following days. The study was approved by the institutional review board of our center and conducted in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients before capsule endoscopy.

Results

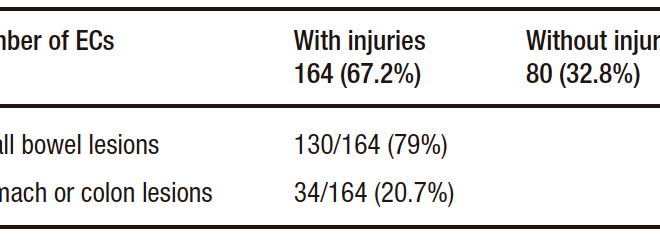

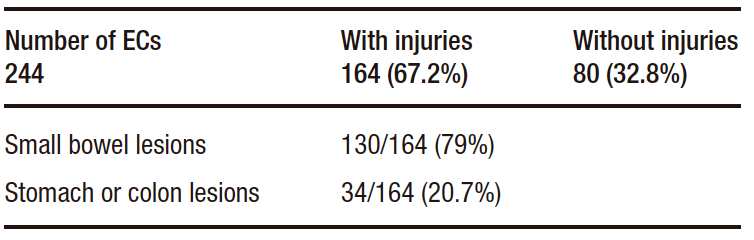

Of the 244 EC procedures, lesions were found in 164 (67.2%). In 130 of these 164 cases, the lesions were located in the SB (53% of the total cases or 79% of the cases with lesions). In 34 of the 244 cases (13.9%) or 34 of the 164 cases with lesions (20.7%), the lesions were found outside the SB (colon or stomach). And in 80 of the 244 cases (32.7%) no injurie or disease was found by the EC (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics

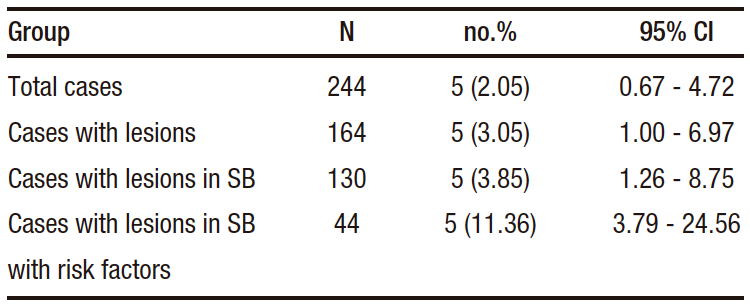

Permanent capsule retention was observed in 5 cases (2.04%). Temporary or permanent retention occurred in 7 of the 130 cases with SB disease (5.3%). Of these 130 cases with SB lesions, 44 (33.8%) had lesions considered to be RF. The CE was retained in 7 of these 44 cases (15.9%), temporarily in 2 (4.5%) and definitively in 5 (11.4%). None of these patients presented with abdominal distension on physical examination (Table 2).

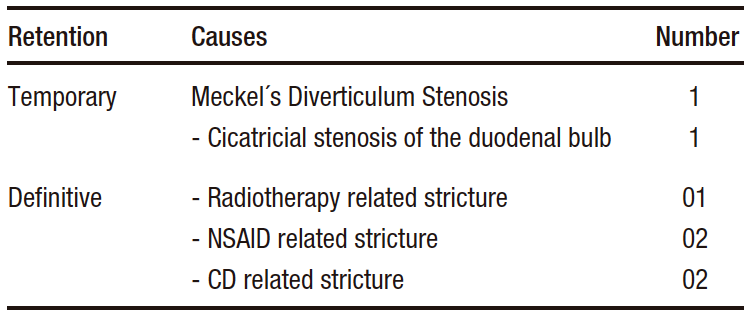

Causes of retention: The 2 cases of temporary retention occurred in a patient with Meckel‘s diverticulum and another with a duodenal bulb deformity (post-ulcer scar). None of these patients were symptomatic after the procedure. The 5 cases of definitive retention occurred in patients with Crohn’s disease (n=2), NSAIDs related stricture (n=2) and 1 case of actinic enteritis. None of these patients presented with clinical signs and symptoms of small bowel obstruction. In the 11 cases of SB malignancy found in 130 patients with SB lesions there was no EC retention (Table 3).

Table 3. Causes of capsule retention

Treatment of retention: The 5 patients with definitive EC retention underwent surgery to remove the device as well as treatment of the underlying lesion. In 2 of them, removal by enteroscopy has been attempted previously without success. All patients had a rapid and complete postoperative recovery.

Discussion

EC retention rates range from 0% to 21% in different series.12, 23, 26- 33 Permanent capsule retention was observed in 5 cases (2.04%) of the total sample. Temporary or permanent retention occurred in 7 out of 130 cases with SB disease (5.3%). However, 44 (33.8%) of the 130 cases had lesions that were considered risk factors for retention. EC was retained in 7 of these 44 cases (15.9%), temporarily in 2 (4.5%) and definitively in 5 (11.4%), or 1 in 10 patients with RF retention had this complication. Definitive retention occurred exclusively in patients with SB strictures of benign etiology.

In Crohn’s disease (CD), EC has become an important tool for the evaluation of SB,1, 2, 19 both in patients with suspected or with already established disease.17 It has become the procedure of choice due to its safety and high diagnostic capacity, especially when ileocolonoscopy is negative.1, 3, 19 However, the safety of EC in patients with Crohn’s disease remains a concern, as the stenosis typically seen in CD may promote EC retention.17 Known SB strictures are considered a contraindication to EC examination.17 If a stenosis is suspected, further imaging studies should be performed prior EC,17, 34-35 such as CT scan (multislice enterotomography) or MR. A previous study showed that in 14 cases of stricture-associated retention, in 11 of them the contrast radiologic examination of the SB did not show stenosis in any of them,4 as was the case in our experience, demonstrating that SB series should no longer be used prior to EC.36

Patients with a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease have a much higher retention rate than patients with suspected Crohn’s disease. In three studies the mean retention was 4%, 6% and 7%, despite normal radiologic studies prior to EC.29, 30, 32 Another study17 reviewed the records of 983 EC tests and selected 102 cases in which the test was performed with suspected Crohn’s disease (64 cases) or already diagnosed Crohn’s disease (38 cases). In one of the 64 cases with suspected Crohn’s disease, EC retention occurred (1.6%), compared with 5 (13%) patients with known CD.17 In 1291 patients who underwent EC, retention occurred in 32 (2.5%). Crohn’s disease and malignancy were the 2 most common causes of retention.2 Many studies have focused on retention as a complication of EC itself. On the other hand, some authors have even questioned whether retention is a complication or a step towards resolution of the clinical situation.8-9, 13-14, 24-25, 41-43, 46 In one study, the authors found that in 4 of the 5 cases in which the EC was retained, there was a clear clinical benefit from the information provided by the EC or the surgical procedure, resulting from the diagnosis of the stenosis highlighted by the EC retention.46 Retention may indicate definitive surgical treatment of the underlying disease. If the stenosis is not less than 2/3 of the diameter of the EC, the EC may eventually pass.2 Elective surgical removal of a retained EC and the stenosis causing its retention, may resolve the clinical picture itself.17,23,26,30,45

An accurate medical history to identify symptoms suggestive of SB strictures and prior radiologic imaging of the SB by CT are indicated before CE, in order to reduce the retention rate. Pseudocapsules or patency capsules could also be used.

Another fact related to technical problems with EC is a possible delay in its passage through the stomach, delaying its arrival at the SB and often preventing a complete SB study. In patients with suspected delayed gastric emptying, such as diabetic gastroparesis, some authors recommend the use of prokinetics before the patient ingests the EC.44

In the case of EC retention, several measures could be taken. In a study analyzing 14 retentions cases, the EC was removed surgically in 11 of 13 cases, by enteroscopy in 1 case and by colonoscopy in another case. One patient refused to have the device removed and was followed for 3 years without developing any clinical picture related to SB obstruction.4 Other authors reported retention in 5 of 245 cases (2%), with 2 cases of Crohn’s disease, 1 SB adenocarcinoma, 1 idiopathic stenosis and 1 case of adhesions.46 In 2 of these cases, the EC was removed by endoscopy and in the other 3, surgical resection was performed.46 In cases of retention, other measures besides endoscopy and surgery could be undertaken. The capsule could be left in place and in case of symptoms of obstruction, surgical or medical treatment should be performed. In patients with Crohn’s disease, steroids and/or biological agents could be used in cases of non-fibrotic strictures. Endoscopic intervention by enteroscopy or surgery with simultaneous removal of the capsule and the stenotic area are the most commonly used therapeutic maneuvers.

In conclusion, retention of EC, although a major complication, is relatively rare (2.04%) in a general population of EC patients. Recognition of risk factors and detailed examination of the small bowel by entero-CT or MR prior to EC are of paramount importance, as CE retention occurs almost exclusively in patients with SB strictures. Small bowel series should no longer be used prior to EC.

Consent for Publication. Anonymized data were used for the elaboration of this article, which did not distort its scientific value.

Intellectual Property. The authors declare that the data and tables that appear in this article are original and were made in their belonging institutions.

Funding. The authors declare that there were no external sources of funding.

Conflict of Interest. The author declares that they have no conflicts of interest in relation to this article.

Copyright

© 2023 Acta Gastroenterológica latinoamericana. This is an open-access article released under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license, which allows non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction, provided the original author and source are acknowledged.

Cite this article as: Saul C, Pereira Lima G, Pacurucu Merchan A et al. Endoscopic Capsule Retention: Frequency, Causes and Risk Factors Analysis in 244 Consecutive Procedures. Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam. 2023;53(2):164-168. https://doi.org/ 10.52787/agl.v53i2.307

References

- Fidder HH, Nadler M, Labat A. The utility of capsule endoscopy in the diagnosis of Crohn disease based on patient’s symptoms. J Clin Gastroenterol 2007;41:384-387.

- Cheon JH, Kim Ys, Lee IS, D K Chang, J-K Ryu, K J Lee, et al. Can we predict spontaneous passage after retention? A Nationwide study to evaluate the incidence and clinical outcomes of capsule endoscopy. Endoscopy 2007;30:1046-52.

- Pennazio M, Spada C, Eliakim R, Keuchel M, May A, Mulder C, et al. Small-bowel capsule endoscopy and device-assisted enteroscopy for diagnosis and treatment of small-bowel disorders: ESGE Clinical Guideline Endoscopy 2015;47:352-376.

- Rondonotti E, Herrerias JM, Penazzio M, Caunedo A, Mascarenhas-Saraiva M, de Franchis R. Complications, limitations and failures of capsule endoscopy: a review of 733 cases. Gastrointest Endoscopy 2005;62:712-716.

- Saschden R, Mammen A, Cave D. Incomplete small intestinal transit and retained videocapsule: a cloud with a silver lining [abstract]. Proceedings of the 3rd international conference on capsule. 2004. February 29 – March 3 Miami Endoscopy 2004.

- Chong AK, Miller A, Taylor A, Desmond P. Randomised controlled trial of polyethilenun glycol administration prior to capsule endoscopy [abstract]. Proceedings of the 3rd international conference on capsule 2004 February 29 – March 3 Miami Endoscopy 2004.

- Cave D, Legnani P, de Franchis R, B S Lewis. ICCE consensus for capsule retention. Endoscopy 2005;37:1065-67.

- Swain P, Adler D, Enns R. Capsule endoscopy in obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy 2005;37:655-59.

- Scapa E, Jacob H, Lemkovicz S, Migdal M, Gat D, Gluckhovski A, et al. Initial experience of WCE for evaluating occult gastrointestinal bleeding and suspected small bowel pathology. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2776-79.

- Carey EJ, Leighton JA, Heigh RI, Schiff AD, Sharma VK, Fleisher DE. Single center outcome of 260 consecutive patients undergoing CE for obscure GI bleeding [abstract] GastrointestEndosc. 2004;59:727

- Gerson LB, Fidler JL, Cave, Leighton JA. ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Small Bowel Bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1265-1287.

- Fireman Z, Mahajima E,Broide E, Shapiro M, Fich L, Sternberget A, et al. Diagnosing small bowel Crohn’s Disease with Wireless capsule endoscopy. GUT. 2003;42:390-2.

- Shim NK, Kim YS, Kim KY, Kim YH, Kim TI, Do JH, et al. Abdominal pain accompanied by weight loss may increase the diagnostic yield of capsule endoscopy: A Korean multicenter study. Scand J Gastroenterol 2006;41:983-88.

- Fry LC, Carey EJ, Schff AD, Heigh RI, Sharma VK, Post JK, et al. The yeld of capsule endoscopy in patient with pain or diarrhea. Endoscopy 2006;38:498-502.

- MishkinDS, Chuttani R, Croffie J, Disario J, Liu J, Shah R, et al. Technology status evoluationreport: Wireless capsule endoscopy. GastrointestEndosc. 2002;56:621-4.

- Leighton JA, Goldstein J, Hirota W, Jacobson BC, Johanson JF, Mallery JS, et al. (Standard of practice committee of the ASGE) Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. GastrointestEndosc. 2003;58:650-5.

- Cheifetz AZ, Kornbluth AA, Legnani P. The risk of retention of capsule endoscopy in patient with know or suspected Crohn’s Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2222.

- Loften EV. Capsule endoscopy for Crohn’s Disease. Ready for prime time? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;2:14-26.

- Enns R, Hookey L, Armstrong D, Bernstein C, Heitman S, Teshima C, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Use of Video Capsule Endoscopy Gastroenterology 2017;152:497-51.

- Fleisher DE, Heigh RI, Nguyen CC, Leighton J, Sharma VK and Musil D. Videocapsuleimpactation at the cricopharingeus: first report of this complication and succesful resolution. GastrointestEndosc. 2003;57:427-8.

- Feitoza AB,Gostout CJ, Kuipshild MA, Rajan E. Videocapsuleendoscopy: is the recording time ideal ? [abstract] Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:5307.

- Gostzak Y, Lautsberg L, Oder HS. Videocapsule entrapped in a Meckel’s diverticulum. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;37:270-1.

- Cheifetz AS, Sachar DB, Lewis BL. Small bowel obstruction: Indication or contraindication for CE? GastrointestEndosc. 2004;59:(suppl )A 6461.

- Liao Z, Jao R, Xu Cl. Indication and detection, complication, and retention rates of small bowel CE: a systematic review. GastrointestEndosc. 2010;71:280-86.

- Cheifetz AS, Lewis BS. Capsule endoscopy retention: Is it a complication? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:688-91.

- Barkin J, Friedmann S, Wireless CE retention requering surgical intervenction: the world experience [abstract] Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:S-928

- Eliachin R, Fischer D, Suissa A, Yassin K, Katz D, Guttman N, et al. Wireless capsule endoscopy is a superior diagnostic tool in comparision to barium followthrough and computerized tomography in patients with Crohn’s Disease suspected. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003;15:853-7.

- Herrerias JM, Caunedo A, Rodrigues-Tellez M, Pellicer F, Herrerías JM Jr. Capsule endoscopy in patients with suspected Crohn’s disease and negative endoscopy. Endoscopy 2003;25:564-8.

- Mow WS, Lo SK, Targan SR, Dubinsky M, Treyzon L, Abreu-Martin M, et al. Initial experience with wireless capsule endoscopy in the diagnosis and management of inflamatory bowel disease.Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;2:31-40.

- Buchman AL, Miller FH, Wallin A, Chowdhry A, Ahn C. Videocapsule endoscopy versus barium contrast studies for the diagnosis of Crohn’s Disease recurrence involving the small intestine. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2171-7.

- Sant’Ana AM, Dubois J, Miron M, Seidman E. Wireless capsule endoscopy for obscure small bowel disorders: Final results of the first pediatric controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005;3:264-70.

- Voderholzer WA, Beinhoelze J, Rogalla P, Murrer S, Schachschal G, Lochs H, et al. Small bowel involvement in Crohn’s Disease: A prospective comparition of WCE and computed tomography enteroclysis. GUT 2005;54:369-73.

- Marmo R, Rotandano G, Pircapo R, et al. CE versus enteroclysis in detection of small bowel involvement in Crohn’s disease: A prospective trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005;3:772-6.

- Vanfleteren L, van der Scharr P, Goedhard J. Ileus related to wireless capsule retention in suspected Crohn’s Disease: emergency surgery obviatedby early pharmacological treatment. Endoscopy 2009;41:E135-E135.

- Voderholzer WA. The role of PillCam endoscopy in Crohn’s Disease: The European experience. GastrointestEndosc. Clin N Am. 2006; 16:287-297.

- O’Longhlin C, BarkinJS. Wireless CE: summary. Gastrointest Endosc. Clin N Am 2004;14:229-37.

- Delvaux M, Soussan E, Laurent V, Lerebours E, Gay G. Clinical evaluation of the use of M2A patency capsule system before a capsule endoscopy procedure, in patient with known or suspected intestinal stenosis. Endoscopy. 2005;37:801-807.

- Spada C, Spera G, Riccioni M, BianconeL, Petruzziello L, Tringali A, et al. A novel diagnostic tool for detecting functional patency of the small bowel: the Given patency capsule. Endoscopy. 2005;37:793-800.

- Boivin MC, Lochs H, Voderholzer WA. Does passage of a patency capsule indicate small bowel patency? A prospective clinical trial. Endoscopy. 2005;37:808-15.

- Signorelli C, Rondonotti E, Villa F, Abbiati C, Beccari G, Avesani E C, et al. Use of the Given patency system for the screening of patients at high risk for capsule retention. Dig Liver Dis 2006;38:326-30.

- Ho KK, Joyce AM. Complications of capsule endoscopy. GastrointestEndosc. Clin N Am 2007;17:169-178,VIII-IX.

- Li F, Gurudu S, De Petris G, Sharma V, Shiff A, Heigh R, et al. Retention of the capsule endoscopy: a single center experience of 1000 CE procedures. GastrointestEndosc. 2008;60:174-8.

- Boyren M, Ritter M. Small bowel obstruction from capsule endoscopy. West J Emerg Med. 2010;11:71-73.

- Saul C. Can the prokinetic reduce the time of passage of the endoscopic capsule by the stomach without speeding up the passage through the small intestine? Endoscopy. 2018;.50: 106-106.

- Pennazio M, Santucci R, Rondonotti E, Abbiati C, Beccari G, Rossini F, et al. Outcome of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after CE: Report of 100 consecutives cases. Gastroenterology 2004;126:643-53.

- Baichi MM, Manthy S. What we have learned from 5 cases of permanent capsule endoscopy retention Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:283-87.

Correspondence: Abdon Pacurucu Merchan

Email: abdon.pm@hotmail.com

Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam 2023;53(2):164-168

Revista ACTA Órgano Oficial de SAGE

Revista ACTA Órgano Oficial de SAGE