Alexandre L Cardoso,1 Ana G A Figueiredo,1 Lara G D Sales,1 Adozina M Souza Neta,1 Íkaro D C Barreto,2 Leda M D F Trindade1

1Medicine Department, Tiradentes University. Aracaju.

2Estatistics. Rural Federal University of Pernambuco. Recife, Brazil.

Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam 2018;48(3):197-205

Recibido: 24/09/2017 / Aprobado: 24/04/2018 / Publicado en www.actagastro.org el 17/09/2018

Summary

Background & aims. gastroesophageal reflux disease elapses from a backflow of gastroduodenal contents. It causes symptoms that compromise quality of life. The study aims to define the prevalence of the disease, sociodemographic profile, clinical manifestation and quality of life. Material and methods. Cross-sectional study. Probabilistic sample of 501 university students with clinical manifestation. It was used clinical, sociodemographic and disease-related quality of life questionnaires. Results. 59 (11.8%) students with the disease, median age 24.5 (range: 20-29), female 49 (83%). Asian: 3.35-fold higher risk, 32% ingested alcoholic beverages. Signs and symptoms: heartburn 40%, regurgitation 41%, throat clearing 36%, chronic cough 53%, chest pain 33%; tonsillitis 44%, hoarseness 45%, asthma 19% and laryngitis 80%. Higher risk: heartburn 2 or more times per week (CI95%: 7.93-418.7; p < 0.001), 3 or more times per week (CI95%: 6.87-419.0; p < 0.001), and regurgitation 2 or more times per week (CI95%: 2.45-16.89; p < 0.001), 3 or more times per week (CI95%: 2.16-19.13; p < 0.001) up to 8 weeks (CI95%: 1.21-10.14; p < 0.006). Higher means to the group Pain (SD: 1.45) and Functional aspect (SD: 1.20). Conclusion. It is worrying the prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease and the contribution for impairment of the individuals’ quality of life.

Key words. Gastroesophageal reflux disease, typical and atypical symptoms, quality of life.

Enfermedad por reflujo gastresofágico: prevalencia y calidad de vida en estudiantes universitarios del área de la salud

Resumen

La enfermedad por reflujo gastroesofágico (ERGE) se produce como consecuencia del reflujo patológico del contenido gástrico al esófago, y causa signos y síntomas que comprometen la calidad de vida. El estudio desea definir la pre valencia de la enfermedad, el perfil sociodemográfico, las manifestaciones clínicas y la calidad de vida del estudiante universitario que sufre esta patología. Material y métodos. Diseño: estudio de corte transversal. Muestra probabilística: 501 estudiantes universitarios con manifestaciones clínicas. Fueron utilizados cuestionarios clínicos, sociodemográficos y de calidad de vida relacionados con la enfermedad. Resultados. 59 estudiantes tenían ERGE (11,8%), edad mediana de 24,5 años (rango: 20-29), 49 de sexo femenino (83%). Los asiáticos tuvieron 3,35 más riesgo; se registró ingesta de alcohol en el 32% de los estudiantes. Signos y síntomas: pirosis el 40%; regurgitación el 41%; cosquilleo crónico de la garganta el 36%; tos crónica el 53%; dolor en el pecho el 33%; amigdalitis 44%; ronquera el 45%; asma el 19% y laringitis el 80%. Mayor riesgo: pirosis 2 o más veces por semana (IC95%: 7,93-418,7; p < 0,001), 3 o más veces por semana (IC95%: 6,87-419.0; p < 0,001), y regurgitación 2 o más veces por semana (IC95%: 2,45-16,89; p < 0,001), 3 o más veces por semana (IC95%: 2,16-19,13; p < 0,001), hasta 8 semanas (IC95%: 1,21- 10,14; p < 0,006). Más altos valores del grupo para el síntoma dolor (SD: 1,45) y el aspecto funcional (1,20). Conclusiones. Preocupa la prevalencia de la enfermedad por reflujo gastroesofágico en los estudiantes y cómo afecta de forma negativa su calidad de vida.

Palabras claves. Enfermedad por reflujo gastroesofágico, síntomas típicos y atípicos, calidad de vida.

Abbreviations

GERD: gastroesophageal reflux disease.

GERD-HRQoL: quality of life scale health related to gastroesophageal reflux disease.

HBQoL: heartburn specific quality of life instrument.

PPI: proton-pump inhibitors.

The gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a chronic condition that elapses from a backflow of gastroduodenal contents to the esophagus or adjacent organs, causing a variable range of symptoms and signs either associated or not with tissue lesions and quality of life impairment.1 Most episodes are postprandial, occurs on distal esophagus, and are short and asymptomatic.2

GERD is a highly prevalent condition in western countries,3 in Brazil correspond to 12% of people who lives in urban areas.4 This disease is more frequent among people 55 years and older and its complications, like erosive esophagitis, are common in white males.5

GERD is a multifactorial process that depends on the anti-reflux barrier, esophageal clearance, esophageal mucosa resistance or emptying and intragastric pressure or both.6

Studies report a connection of heartburn between complains of “sour or bitter taste in the mouth” and dietary intake, higher prevalence in females, stress, low well-being index, low educational levels, affective problems, insomnia, fatty food, fried food, seasonings and overweight/obesity.7, 8

The clinical picture is generally characterized by heartburn and regurgitation, considered typical symptoms. Heartburn is presented like a burning sensation on retrosternal portion that radiates from the sternal manubrium to the base of the neck, can reach the throat and/or acid regurgitation.9 Stress is widely recognized as a negative factor for heartburn, most likely for an amplifying effect of the symptom instead of gastroesophageal reflux increase.10

Atypical manifestation might appear individually, becoming even harder the diagnostic investigation.11 Some patients report dyspeptic associated symptoms like postprandial bloating, gastric fullness, belching and nausea. If the patient report typical symptoms at least two times per week in a four to eight weeks period or more, GERD diagnosis should be suspected.9 The proton-pump inhibitors therapeutic test can empirically diagnose GERD.11 The upper gastrointestinal endoscopy should be indicated specially in response to alarming manifestations, besides severe symptoms or worsening at night.9, 12 Functional evaluation methods like esophageal manometry and esophageal pH-metry are used to offer better accuracy in GERD diagnostic.13

The impact on affected individual’s quality of life and negative consequences on the social and working activities is considered an important factor in GERD evaluation.11, 14 Such, impact is associated with pain, discomfort, sedentariness, impairment of daily life and social relations, diet patterns, impact on productivity, especially when associated to sleep deprivation.15

This study aims at assessing GERD prevalence, epidemiologic profile, clinical manifestation and health sciences students of a private university quality of life.

Material and methods

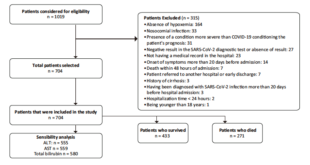

Cross-sectional study conducted from January to May 2016 in Tiradentes University, Aracaju, Sergipe, Brazil, the sample consisted of 750 graduate students in medicine, odontology, nursing and physiotherapy in the last two years of college. Of those students, only 501 answered the research tools. Probability sampling. Diagnostic criteria for GERD: previous diagnostic; presence of heartburn or regurgitation or both at least two times per week during four to eight weeks; individual that presented regurgitation or not, since they meet the heartburn criteria. Were included in the research all students that presented previous diagnostic and typical and/or atypical manifestation of the disease.

It was used three self-administered questionnaires: sociodemographic and clinical profile (elaborated by the authors), quality of life scale health related to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD-HRQoL) and heartburn specific quality of life instrument (HBQoL), both validated into Portuguese.

For the individuals that presented heartburn and/ or regurgitation clinical criteria it was used the GERD-HRQoL questionnaire and for those regardless of presenting regurgitation or not, but presented heartburn/pyrosis it was used HBQoL, which is an instrument to evaluate the heartburn influence in nine domains of quality of life. The studied domains were: pain, sleep diet, vitality, social aspect, physical aspect, work, general state of health and mental health. There is a question for which domain of HBQoL, except for physical aspect, pain, sleep and diet that presents two or more questions. An individual score was received for each Quality of Life domain, just one question for GERD-HRQoL and nine for HBQoL. The results were reported using simple and percentage frequency for categorical data, mean and standard deviation for continuous data. It was used Mann-Whitney test to evaluate differences of mean and for possible associations between variables chi-square test. The statistical significance level was established as 5% and the software used was R Core Team 2016. The study was approved by Universidade Tiradentes Research Ethics Committee (Comitê de Ética e Pesquisa da Universidade Tiradentes), CAAE 48329215.6.0000.537. All participants signed a written informed consent.

Results

The groups were classified accordingly to the semester: 154 nursing students and 91 physiotherapy students were among seventh, eighth, ninth and tenth semester; 100 medicine students were between ninth and eleventh semester and odontology students among sixth, seventh, eighth and ninth semester. The groups were classified accordingly to the semester/year of admission, and 161 (32.1%) were in the ninth semester.

From the students, 59 (11.8%) were classified with GERD and/or had been previously diagnosed, while 442 (88.2%) did not meet the clinical criteria for the diagnostic. The odontology students presented higher symptoms frequency 19 (12%).

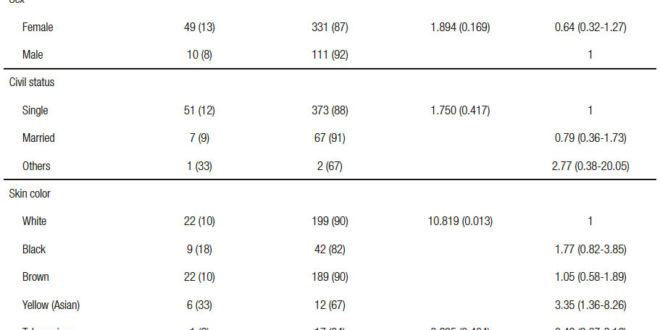

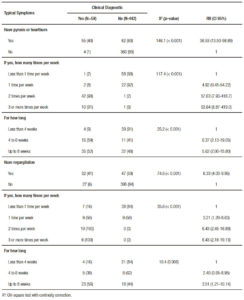

The median age was 24.5 years (range: 20-29). From the disease carriers, 49 (83%) were represented by females; 51 (86%) were single. Concerning ethnic groups, according to Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, 44 (74%) students identified themselves white and brown and 9 (18%) black. For those that identified themselves as yellow (Asian), presented a 3.35-fold greater risk for GERD than white students. 19 (32%) used alcoholic beverages. Only 1 (25%) student was detected with obesity. Those who used proton-pump inhibitor, 14 (64%) presented higher risk for GERD (Table 1).

It was associated with higher relative risk of typical symptoms those who had heartburn two or three times per week in a period of three or more weeks. Claimed to have regurgitation 32 (41%), also associated with higher risk of GERD (p < 0.001) those with symptoms manifestation 2 times per week and 3 or more times per week. The time of disease was associated with higher risk for 23 (56%) of those who presented symptoms up to 8 weeks (Table 2).

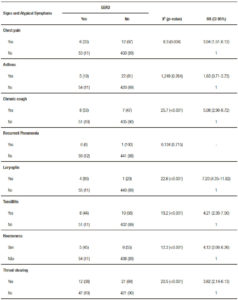

All signs and atypical symptoms presented by the interviewees exhibited statistical relevance when applied the chi-squared test to evaluate the higher risk of association with GERD. Chronic cough 8 (53%), tonsillitis 8 (44%) and throat clearing 12 (36%) were more prevalent (Table 3).

Quality of life and health condition of patients with GERD, regarding the patient satisfaction level with their current situation showed that 20 (33.9%) expressed dissatisfaction and 25 (42.4%) offered a neutral opinion. Only 1 (1.7%) considered himself disabled.

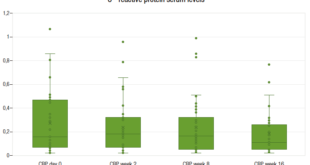

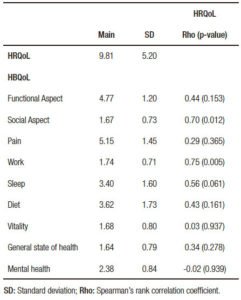

When assessed the relation between symptoms and quality of life, the mean values for GERD-HRQoL was 9.81. On HBQoL was observed higher means for pain domain (5.15) and functional aspects (4.77) and lower means for general state of health (1.64), social aspect (1.67) and vitality (1.68). Analysis of social aspect (p = 0.012) and work (p = 0.005), according the GERD-HRQoL and HBQoL domains to the positive, negative, strong or weak correlation showed statistical significance (Table 4).

Table 1. Absolute sample distribution according to sociodemographic profile and student’s habits with or without clinical diagnostic for GERD.

Table 2. Absolute sample distribution according to sociodemographic profile and student’s habits with or without clinical diagnostic for GERD.

Table 3. Absolute sample distribution according to atypical symptoms on students with or without diagnostic for GERD.

Table 4. Correlation between symptoms and quality of life related to health according to GERD-HRQoL and HBQoL domains.

Discussion

GERD can compromise the quality of life of its patients.14 In this study, prevalence of GERD was 11.8%, corroborating data in literature. Population survey conducted in 22 cities of Brazil, with 13,950 individuals sample identified a prevalence of 11.8%.9

Odontology (19-12%) and medicine (15-15%) students were those who presented the most clinical diagnostic for GERD, however, odontology students were more affected by symptoms. It was not found studies comparing GERD among the assessed groups. Higher disease frequency was identified among females, correlated to stress factors and single individuals.16 According to Suzuki et al.4 the disease is more frequent in individuals above 55 years, however, in our study, the main age was 24.5 years, yet must be consider that it is a younger population. White and brown skin were statistically relevant (p = 0.001). The study data showed students that identified themselves as yellow (Asian) presented 3.35- fold higher risk for GERD than white skin students. Some authors report a prevalence of 43% black, 34% white and 23% other ethnic groups,17 though other authors point out higher prevalence among white.18-19

There was no statistical significance related to life habits, which differs from Fraga et al. that claimed that tobaccoism and excessive alcohol consumption were risk factors for GERD development.16

In a western population controlled, study showed that heartburn and/or regurgitation was prevalent around 20 to 40% related to occurrence time being at least one time per week.11, 16 However, in the studied group, the disease time was associated with higher risk to 23 (56%) of those that presented heartburn and regurgitation up to 8 weeks.

All signs and atypical symptoms presented by the interviewees showed statistical relevance, besides higher risk of GERD association and the most prevalent was chronic cough 8 (53%), tonsillitis 8 (44%) and throat clearing 12 (36%). Nasi et al. evaluated 200 patients and identified the presence of atypical symptoms in 23.5% of them, while 52.5% presented typical symptoms.20

Obesity, comorbidity considered risk factor, was identified in one student 1 (25%). Overweight is associated to increased intra-abdominal pressure that elevates the gastroesophageal pressure gradients and intragastric pressure.6-16

Inhibition of gastric acid secretion is indeed benefic on GERD treatment11, 21 and it is considered first-line therapy in several studies.22

In a study with 111 patients comparing use of antacids and placebo was observed that the use of medication relieved 62% of cases of chest pain associated with GERD.23 According to Brazilian Federation of Gastroenterology.24 such medications are recommended for treatment of patients with symptomatic GERD. However, in the study in question, use of proton-pump inhibitors (PPI) did not present a positive impact on affected student’s life. For those on PPI, 14 (64%) of them presented higher risk for GERD.

There are only five questionnaires in the medical literature to evaluate symptoms and quality of life of patients with GERD, although none of them present a full evaluation.25 In the studied group, the main of values found in GERD-HRQoL was 9.81, with a standard deviation of 5.20 that indicates a slightly compromise in quality of life. Regarding the degree of patient satisfaction in the moment of the interview, 20 (33.9%) were unsatisfied and 25 (42.4%) neutral.

A significant statistical difference (p < 0.001) was found among all domains assessed by HBQoL. The do main with higher value was pain, revealing that students suffer from severe to moderate heartburn. GERD presence seems to negatively impact on student’s quality of sleep and diet.

Concerning the physical domain, the patients related a reduction of time spent in work. Another domain that was affected was the social disease which seemed to interfere on social activities.

Vitality and general state of health domains from individuals with GERD was compromised on those that related fatigue. The work and mental health domains were also compromised, while in the later, students reported that heartburn worry and afflicted them in moderate to mild degrees. Such findings confirm evidences observed, which GERD patients present some degree of quality of life impairment, both in general and in relation to several domains.26

Suzuki et al.4 suggest that for a better population analysis, other criteria must be used, such as diet pattern and medication use. In a study conducted by Almeida et al. when applied HBQoL questionnaire, could be observed quality of life impairment in GERD patients and how treatment can cause a positive effect on this group.18-19

As regard to the satisfaction level, showed divergent data from those observed for Andrade et al.14 in which much of studied patients were satisfied with their condition, whereas in this study, 25% claimed to be neutral considering the symptoms impact on quality of life.

The anamnesis was the prime tool to select the sample of this study. However, some limitations are to be considered, such as, sample size, concrete data of specific exams (Ph-metry and endoscopy), absence of questioning related to non-pharmacological practices and possible surgical procedures, which in some studies present positive impact on symptomatic patient’s quality of life.20, 27

Conclusion

From medical history is possible to identify GERD patients. The prevalence of the disease kept in accordance with other studies of general population. Typical symptoms like heartburn and regurgitation and atypical symptoms like chronic cough, tonsillitis and throat clearing were more prevalent, while other pulmonary and otorhinolaryngology symptoms are responsible for the incidence of disease. Added to this, female, single and alcohol consumption. The general state of health was more compromised on those who presented heartburn. Quality of life can be impaired as the symptoms limit daily activities, depending on symptoms intensity and disease progress.

Funding. The funding of this study was totally financed by the authors.

References

- Federação Brasileira de Gastroenterologia. Refluxo gastroesofágico: diagnóstico e tratamento. Rev AMRIGS 2006; 50: 251-263.

- Ratier JCA, Pizzichini E, Pizzichini M. Doença do refluxo gastroesofágico e hiperresponsividade das vias aéreas: coexistência além da chance? J Bras Pneumol 2011; 37: 680-688.

- Savarino V. Update in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol 2017; 63: 172-174.

- Suzuki NM, Nakae TK, Castro PC, Bonadia JCA. Doença do Refluxo Gastroesofágico (DRGE): epidemiologia e qualidade de vida em estudantes universitários. Arq Med Hosp Fac Cienc Méd Santa Casa São Paulo 2011; 56: 65-67.

- Boeckxstaens G, El-Serag HB, Smout AJPM, Kahrilas PJ. Symptomatic reflux disease: the present, the past and the future. Gut 2014; 63: 1185-1193.

- Biccas BN, Lemme EMO, Abrahão Jr LJ, Aguero GC, Alvariz AC, Schechter RB. Maior prevalência de obesidade na doença do refluxo gastroesofagiano erosiva. Arq Gastroenterol 2009; 46: 15-19.

- Barros SGS. Doença do refluxo gastroesofágico – prevalência, fatores de risco e desafios. Arq Gastroenterol 2005; 42: 71.

- Oliveira SS, Santos IS, Silva JFP, Machado EC. Prevalência e fatores associados à doença do refluxo gastroesofágico. Arq Gastroenterol 2005; 42: 116-121.

- Henry MACA. Diagnóstico e tratamento da doença do refluxo gastroesofágico. ABCD Arq Bras Cir Dig 2014; 27: 210-215.

- Abrahão LJ Jr. Doença do refluxo gastroesofágico. J Bras Med 2014; 102: 31-36.

- Moraes-Filho JPP, Domingues G. Doença do refluxo gastroesofágico. RBM Rev Bras Med 2009; 66: 303-310.

- Matei D, Groza I, Furnea B, Puie L, Levi C, Chiru A, Cruciat C, Mester G, Vesa SC, Tantau M. Predictors of variceal or non-variceal source of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. An etiology predictive score established and validated in a tertiary Referral Center. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2013; 22: 379-384.

- Andreollo NA, Lopes LR, Coelho-Neto JS. Doença do refluxo gastroesofágico: qual a eficácia dos exames no diagnóstico? ABCD Arq Bras Cir Dig 2010; 23: 6-10.

- Andrade FJC, Almeida ER, Santos MTBR, Soares-Filho E, Lopes JB, Veras e Silva RC. Qualidade de vida do paciente submetido à cirurgia videolaparoscópica para tratamento para doença do refluxo gastroesofágico. ABCD Arq Bras Cir Dig 2012; 25: 154-160.

- Caviglia R, Ribolsi M, Maggiano N, Gabbrielli AM, Emerenziani S, Guarino MP, Carotti S, Habib FI, Rabitti C, Cicala M. Dilated intercellular spaces of esophageal epithelium in nonerosive reflux disease patients with physiological esophageal acid exposure. Am J Gastroenterol 2005; 100: 543-548.

- Fraga PL, Martins FSC. Doença do Refluxo Gastroesofágico: uma revisão de literatura. Cadernos UniFOA 2012; 18: 93-99.

- El-Serag HB, Petersen NJ, Carter J, Graham DY, Richardson P, Genta RM, Rabeneck L. Gastroesophageal reflux among different racial groups in the United States. Gastroenterology 2004; 126: 1692-1699.

- Almeida LC, Barros RLBS, Almeida e Silva K, Andrade VLA. Efetividade do tratamento osteopático na qualidade de vida e na percepção dos sintomas de pacientes com doença de refluxo gastroesofágico refratária ao tratamento medicamentoso. GED Gastroenterol Endosc Dig 2014; 34: 10-17.

- Federação Brasileira de Gastroenterologia, Sociedade Bra¬sileira de Endoscopia Digestiva, Colégio Brasileiro de Ci¬rurgia Digestiva, Sociedade Brasileira de Pneumologia e Tisiologia. Doença do refluxo gastroesofágico: diagnóstico. AMB Rev Assoc Med Bras 2011; 57: 499-507.

- Nasi A. DRGE não responsiva a IBP: qual a conduta? J Bras Med 2015; 103: 22-24.

- Majithia R, Johnson DA. Are proton pump inhibitors safe during pregnancy and lactation? Evidence to date. Drugs 2012; 72: 171- 179.

- Ganz RA, Peters JH, Horgan S, Bemelman WA, Dunst CM, Edmundowicz SA, Lipham JC, Luketich JD, Melvin WS, Oelschlager BK, Schlack-Haerer SC, Smith CD, Smith CC, Dunn D, Taiganides PA. Esophageal sphincter device for gastroesophageal reflux disease. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 719-727.

- Surdea-Blaga T, Băncilă I, Dobru D, Drug V, Frățilă O, Goldiș A, Grad SM, Mureșan C, Nedelcu L, Porr PJ, Sporea I, Dumitrascu DL. Mucosal protective compounds in the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. A position paper based on evidence of the Romanian Society of Neurogastroenterology. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2016; 25: 537-546.

- Federação Brasileira de Gastroenterologia, Sociedade Brasileira de Endoscopia Digestiva, Colégio Brasileiro de Cirurgia Digestiva, Sociedade Brasileira de Pneumologia e Tisiologia. Doença do refluxo gastroesofágico: tratamento farmacológico. AMB Rev Assoc Med Bras 2011; 57: 617-628.

- Velanovich V, Vallance SR, Gusz JR, Tapia FV, Harkabus MA. Quality of life scale for gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Am Coll Surg 1996; 183: 217-224.

- Madisch A, Kulich KR, Malfertheiner P, Ziegler K, Bayerdörffer E, Miehlke S, Labenz J, Carlsson J, Wiklund IK. Impact of reflux disease on general and disease-related quality of life – evidence from a recent comparative methodological study in Germany. Z Gastroenterol 2003; 41: 1137-1143.

- Federação Brasileira de Gastroenterologia, Sociedade Brasileira de Endoscopia Digestiva, Colégio Brasileiro de Cirurgia Digestiva, Sociedade Brasileira de Pneumologia, Associação Brasileira de Otorrinolaringologia e Cirurgia Cérvico-Facial. Doença do refluxo gastroesofágico: tratamento não farmacológico. AMB Rev Assoc Med Bras 2012; 58: 18-24.

Correspondencia: Ana Galrão de Almeida Figueiredo

Av Beira Mar, number 1704, apto 801 (Zip code: 49025040) Aracaju, Sergipe, Brasil.

Tel.: +5579999746465

Correo electrónico: anagalrao.f@gmail.com

Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam 2018;48(3):197-205

Revista ACTA Órgano Oficial de SAGE

Revista ACTA Órgano Oficial de SAGE