María Inés Pinto Sánchez, Elena F Verdú

Farncombe Family Digestive Health Research Institute, McMaster University. Hamilton, Canadá.

Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam 2019;49(2):166-182

Recibido: 12/03/2019 / Aprobado: 20/03/2019 / Publicado en www.actagastro.org el 17/06/2019

Resumen

Desde los primeros reportes hace más de cuarenta años, la sensibilidad al gluten o al trigo no celíaca (SGNC/STNC) se ha convertido en un tema intrigante y controvertido en la gastroenterología. El diagnóstico se basa en la definición de consenso que requiere: 1) una reacción sintomática al gluten/ trigo, 2) la resolución de los síntomas después de la exclusión de alimentos que contienen gluten/trigo y 3) la reaparición de los síntomas con la reintroducción de productos con gluten/trigo. El diagnóstico definitivo de SGNC/STNC es desafiante ya que no hay pruebas o marcadores biológicos específicos y todavía está cuestionado el desencadenante exacto de la enfermedad. Se han realizado varios estudios randomizados y controlados con la intención de comprender si el gluten o la fracción de carbohidratos en el trigo son los que desencadenan los síntomas en pacientes no celíacos. Realizamos una revisión de la literatura para abordar las controversias y los mayores desafíos relacionados con el diagnóstico y el manejo de la SGNC/STNC, así como las áreas de interés para futuros estudios de investigación.

Abreviaturas

SGNC: sensibilidad al gluten no celíaca.

STNC: sensibilidad al trigo no celíaca.

EC: enfermedad celíaca.

ATI: inhibidores de amilasa y tripsina.

FODMAPs: oligosacáridos, disacáridos, monosacáridos y polioles fermentables.

SII: síndrome del intestino irritable.

HLA: antígeno de histocompatibilidad.

TLR: receptor tipo toll.

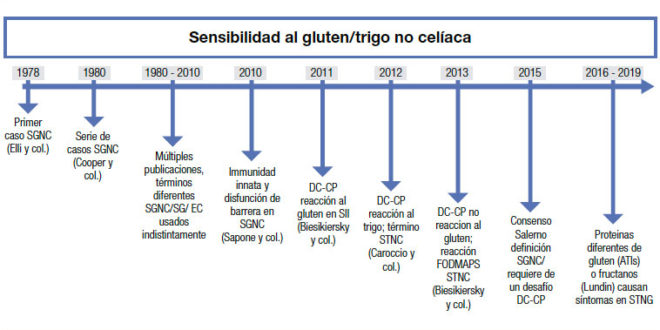

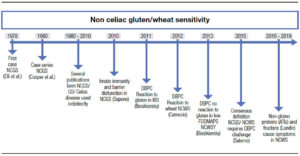

El término “sensibilidad al gluten no celíaca” (SGNC) no es nuevo. Fue acuñado por primera vez hace más de cuarenta años, cuando Ellis y Linaker identificaron el primer caso de diarrea que mejoró con una dieta sin gluten en ausencia de enfermedad celíaca (EC).1 Sin embargo, el nombre “sensibilidad al gluten” se ha usado con frecuencia indistintamente al de EC, lo cual ha generado confusión. La EC se define como una enteropatía autoinmune inducida por el gluten en personas genéticamente susceptibles, y su fisiopatología es bien conocida. A la inversa, el debate sobre la definición y la fisiopatología de la SGNC perdura. Debido al desconocimiento del factor desencadenante, la entidad ha sido recientemente rebautizada como sensibilidad al “trigo” no celíaca (STNC) (Figura 1).2

Figura 1. Historia y avances desde el primer reporte de sensibilidad al gluten no celíaca.

Es importante destacar que el diagnóstico de STNC está basado casi en su totalidad en la presentación clínica y en el reconocimiento del gluten o trigo como inductor de los síntomas. Por lo tanto, el diagnóstico requiere una reacción sintomática al gluten, o a alimentos que contienen trigo, en individuos en los que se ha descartado la EC y la alergia al trigo.3 Por lo tanto, el diagnóstico se basa en la definición de consenso que requiere: 1) una reacción sintomática al gluten/trigo, 2) la resolución de los síntomas después de la exclusión de alimentos que contienen gluten/trigo y 3) la reaparición de los síntomas con reintroducción de productos con gluten/trigo.4 En ausencia de marcadores biológicos validados, un diagnóstico de STNC solo puede hacerse mediante un desafío con gluten/trigo cruzado doble ciego, controlado con placebo; lo cual es sumamente difícil de aplicar en la práctica clínica.5 Además, el estudio de desafío no confirma si los síntomas reconocidos previos al desafío se debieron efectivamente al gluten, a otras proteínas de trigo, carbohidratos u otros componentes en el trigo. De las personas que reportan sensibilidad al gluten o al trigo, solo una pequeña proporción (16%) tendrá síntomas reproducibles después de una prueba cegada de desafío con gluten versus placebo y cumplirán los criterios de consenso actuales para un diagnóstico de SGNC/STNC.5 Esto destaca claramente la dificultad y la controversia en el diagnóstico y el manejo de esta condición. En esta revisión nos centraremos en los desafíos más comunes relacionados con la SGNC/STNC y las áreas que requieren mayor investigación.

Controversias

“Qué hay en un nombre?”

“Eso a lo que llamamos rosa, con cualquier otro nombre conservaría su dulce aroma”. En la obra de William Shakespeare Romeo y Julieta, esto implica que los nombres atribuidos a las cosas no afectan lo que realmente son. El término SGNC/STNC ha generado debate desde los primeros reportes.1 El nombre “sensibilidad al gluten” implica una reactividad inmune al gluten, la fracción proteica inmunogénica en el trigo que le da a la masa su consistencia, y esto ha generado confusión a la hora de diferenciarla de la EC.2 En los últimos años, ha habido varias reuniones de consenso que intentaron redefinir la condición.6-8 Para evitar la confusión con EC, el consenso de Oslo alentó el uso del término SGNC en lugar de “sensibilidad al gluten”.6 El mismo consenso describió una variedad de manifestaciones inmunológicas, morfológicas o sintomáticas precipitadas por la ingestión de gluten en individuos en quienes la EC y la alergia al gluten fueron excluidas. En la misma dirección, Sapone y col. describen la SGNC como una reacción al gluten en la cual se han descartado mecanismos tanto alérgicos como autoinmunes, lo que sugiere que la SGNC sería un diagnóstico de exclusión.7 El consenso de Salerno más reciente introdujo un algoritmo de dos pasos en el que los pacientes deberían mejorar sus síntomas en un período de seis semanas con una dieta libre de gluten (DLG), seguido de un segundo período que requiere de la demostración de recurrencia de los síntomas después del desafío doble ciego controlado con placebo durante una semana.3 El desafío debe realizarse con cápsulas que contengan 8 g de gluten, al menos 0,3 g de inhibidores de amilasa y tripsina (ATI) en un vehículo libre de oligosacáridos, disacáridos, monosacáridos y polioles fermentables (FODMAPs), y como comparador se sugiere placebo sin gluten.3

En una revisión reciente, Catassi y col. introdujeron el término nuevo “síndrome de intestino irritable sensible al gluten o al trigo” que incluye a los pacientes que presentan síntomas de tipo síndrome del intestino irritable (SII) desencadenados por el gluten.8 Además de los síntomas del SII, los pacientes pueden presentar una variedad de síntomas gastrointestinales y extraintestinales. Volta y col. describieron en su estudio que el síntoma extraintestinal más frecuente fue la confusión mental o una “mente confusa”, una sensación de letargia provocada por el gluten, la cual se observa en el 42% de los casos.9, 10 Otros síntomas intestinales adicionales identificados fueron fatiga, erupción cutánea, dolor de cabeza, dolor articular y muscular (síndrome similar a la fibromialgia), entumecimiento de piernas o brazos, depresión, ansiedad y anemia. Por lo tanto, el diagnóstico clínico de SGNC/STNC no es sencillo y, hasta ahora, el diagnóstico más complejo propuesto por el criterio de Salerno no es práctico en la clínica. Cuando a los pacientes con sospecha de SGNC se les realiza un desafío ciego con gluten comparado con placebo como lo sugieren los criterios de Salerno, solo el 22% confirma SGNC.11

Se han utilizado otras pruebas para apoyar el diagnóstico de SGNC. Por ejemplo, estudios de las biopsias duodenales realizadas en pacientes con SGNC muestran una longitud vellositaria normal, con o sin aumento de linfocitos intraepiteliales y menos probable aumento de eosinófilos.11, 12 Si bien algunos autores han sugerido una reacción inmune gatillada por el desafío con gluten, por ejemplo, el aumento de las tasas de basófilos en las biopsias de SGNC13, otros autores no pudieron confirmar estos hallazgos.14

A diferencia de la EC, no existe una serología específica para diagnosticar el SGNC. Los anticuerpos antigliadina se encuentran en aproximadamente el 50% de los pacientes con sospecha de STNC; sin embargo, estos no son específicos y pueden estar presentes en muchas otras afecciones gastrointestinales.7, 9, 10 Algunos estudios sugirieron que genes relacionados con la EC (HLA-DQ2 y DQ8) pueden ser ligeramente más frecuentes en SGNC/ STNC (~ 50%),15 sin embargo, esto ha sido controvertido por otros. En un estudio reciente, Maki y col. evaluaron la presencia de HLA DQ2-DQ8 en cincuenta pacientes con SGNC en comparación con los controles sin SGNC.16 Ellos encontraron que las combinaciones de genotipos más comunes dentro de la cohorte sensible al gluten eran A1-3/B2-6 y A1-5/B2-6, y la primera estaba presente solo en la población con SGNC. Aunque la idea de identificar una predisposición genética para esta condición es alentadora, aún no está claro. Debido a la falta de una presentación clínica clara y pruebas de diagnóstico para identificar el SGNC/STNC; existen claras dificultades para estimar adecuadamente su prevalencia. En un estudio de EE. UU. en el que participaron más de 7000 personas de la población general, Digiacomo y col. identificaron SGNC/STNC en hasta el 6% de la población de los EE. UU.18 Sin embargo, la mayoría de los pacientes que identifican el trigo como el responsable de sus síntomas ya está en una dieta sin gluten o con restricción de trigo cuando consultan a un médico, lo cual dificulta aún más el diagnóstico.17

¿Por qué necesitamos entender los mecanismos involucrados en STNC?

La comprensión de los mecanismos que generan los síntomas es clave para desarrollar investigaciones relevantes para un tratamiento o manejo clínico adecuado. Las enfermedades complejas son en general difíciles de manejar debido a que su mecanismo es multifactorial. Los mecanismos potenciales involucrados en la fisiopatología del SGNC/STNC son múltiples e incluyen, como en el SII, alteraciones en la permeabilidad intestinal, estimulación de la inmunidad innata y cambios en la motilidad gastrointestinal. La principal diferencia entre el SII y el SGNC/STNC sería el desencadenante. Si bien el SII tiene muchos factores desencadenantes, se supone que la disfunción intestinal y la generación de síntomas en el SGNC/STNC son inducidas principalmente por el consumo de gluten/trigo. Como tal, el SGNC/STNC podría considerarse parte del espectro del SII inducido por alimentos. En cuanto al cuadro clínico, otros argumentan que el SGNC/STNC presenta una gran cantidad de síntomas no digestivos (fatiga, etc.) que, aunque también están presentes en algunos pacientes con SII, no definen clínicamente el síndrome, cuyo diagnóstico se limita a síntomas gastrointestinales.9, 10 Por lo tanto, podría plantearse la hipótesis de que se aplican mecanismos específicos al SGNC/STNC que difieren de los del SII. Existe un interés particular en aclarar si la permeabilidad intestinal está alterada en el SGNC/STNC. Un estudio inicial realizado por Sapone y col. no encontró alteraciones en la permeabilidad intestinal en SGNC en comparación con EC.19 Estudios posteriores encontraron resultados opuestos, que pueden estar relacionados con las diferencias en la metodología entre los estudios y, lo que es más importante, con las variaciones en la definición de SGNC, que pueden llevar a un sesgo de selección.20-23

La tolerancia inmune a los antígenos de la dieta es clave para prevenir respuestas indeseables a los antígenos inocuos ingeridos con alimentos; por lo tanto, la pérdida de tolerancia al gluten u otras proteínas del trigo en SGNC/STNC podría implicar un mecanismo mediado por el sistema inmunitario.24, 25 Estudios in vitro han demostrado que la digestión de gliadina aumenta la expresión de moléculas coestimulantes, así como la producción de citoquinas proinflamatorias en monocitos y células dendríticas.26, 27 Otros estudios demostraron una mayor expresión de TLR-2 en la mucosa intestinal de pacientes no celíacos en comparación con pacientes celíacos, lo que sugiere un papel del sistema inmunitario innato en la patogénesis de las reacciones no celíacas al gluten u otros componentes del trigo.19 En un estudio reciente, Gómez Castro y col. demostraron que el péptido p31-43 (p31-43) de la a-gliadina puede inducir una respuesta inmune innata en el intestino y que esto puede iniciar una inmunidad adaptativa patológica.28 El papel de este u otros péptidos inmunogénicos en SGNC/ STNC no está claro aún. Es importante destacar que otras proteínas en el trigo, como los inhibidores de la a-amilasa/tripsina (ATI) y la aglutinina de lectina del trigo, han demostrado recientemente inducir vías de inmunidad innata2 y han abierto el campo a otras proteínas diferentes del gluten que podrían ser responsables de los síntomas en población no celíaca. Existe un interés creciente en el papel de los ATI como activadores de respuestas inmunes innatas en monocitos, macrófagos y células dendríticas a través del complejo 4-MD2-CD14 del receptor tipo toll (TLR).29 Un estudio reciente realizado por Caminero y col.30 ha demostrado una mayor activación inmune en ratones alimentados con gluten y ATI en comparación con aquellos que solo recibieron gluten o solo ATI, lo cual indicaría un posible efecto sinérgico de ambos. Además de las fracciones de proteínas, el trigo contiene un grupo de carbohidratos fermentables, llamados fructanos, que son miembros de FODMAPs y que no se absorben demasiado en el intestino delgado.2 En un estudio posterior, Biesikiersky y col. sugirieron que el gluten no tuvo ningún efecto en pacientes con SGNC después de la reducción de los FODMAPs en la dieta.31 Sin embargo, este estudio incluyó una población mixta de pacientes con SII que probablemente responden a diferentes gatillos, incluido al placebo. Otros problemas metodológicos, como los cortos períodos de washout entre los desafíos, pueden dificultar la interpretación de los resultados. Un estudio reciente de Skodje y col. sugirió que los fructanos en lugar del gluten inducirían síntomas en el STNC.32 Los mecanismos para estas reacciones no se investigaron en ninguno de estos estudios. Los cambios en la motilidad gastrointestinal y la microbiota intestinal se han propuesto como un mecanismo potencial en la SGNC/STNC. Los estudios en animales demostraron que la gliadina puede desencadenar la hipercontractilidad del músculo liso y la disfunción del nervio colinérgico en un modelo de ratones que expresan los genes (HLA) -DQ8 pero sin atrofia duodenal evidente.27 Existen algunos estudios clínicos que han investigado cambios en la motilidad gastrointestinal desencadenados por componentes del trigo. Un estudio inicial de Vázquez Roque demostró en una cohorte de pacientes con SII con diarrea que la dieta sin gluten no tuvo efectos significativos en el tránsito gastrointestinal.21 Sin embargo, un estudio más reciente realizado por nuestro grupo demostró que la normalización de la motilidad gastrointestinal en los pacientes con SII se limitaba a aquellos con anticuerpos antigliadina positivos.33

La búsqueda de gatillo/s en SGNC/STNC es polémica

Una de las áreas más controvertidas en SGNC/STNC es identificar si el gluten, otra proteína de trigo o las fracciones de carbohidratos desencadenan los síntomas. Varios estudios clínicos (Tabla 1), así como estudios en ratones, han intentado abordar este problema con resultados controvertidos. El gluten ha sido un objetivo obvio desde que se describió la enfermedad por primera vez.1 Diferentes estudios randomizados controlados con placebo demostraron que el desafío con el gluten desencadena síntomas gastrointestinales y extraintestinales en pacientes no celíacos.34-40 La principal limitación es que el desafío del gluten rara vez es un desafío puro y, como se señaló anteriormente, el trigo contiene otras proteínas inmunogénicas29, 30 y carbohidratos31, 32 que pueden contribuir a los síntomas en SGNC/STNC solos o mediante un efecto sinérgico. Sin embargo, los estudios clínicos en esta área son escasos. El efecto de una dieta baja en ATI aún no se ha probado en un estudio clínico, y solo hay un estudio que evalúa el papel de los fructanos en pacientes con SGNC/STNC.32 Finalmente, no queda claro por qué algunas personas que están perfectamente sanas de repente experimentan síntomas relacionados con el trigo o el gluten. Aunque los factores predisponentes son desconocidos, se ha sugerido que la disbiosis después de una gastroenteritis podría inducir falta de tolerancia.41 Existen diferentes mecanismos por los cuales los microorganismos pueden proporcionar señales proinflamatorias directas al huésped que promueven la degradación de la tolerancia oral a los antígenos alimentarios, o por vías indirectas que involucran el metabolismo de los antígenos proteicos y otros componentes de la dieta por microorganismos intestinales, lo cual podría explicar las reacciones al trigo.42

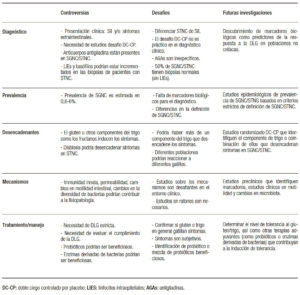

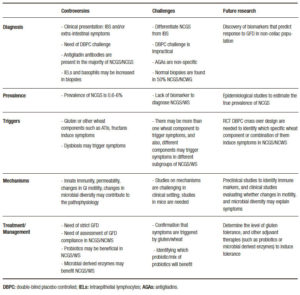

Tabla 1. Resumen de estudios clínicos en SGNC/STNC (Adaptado de Pinto-Sánchez y col., NMO 2018).

¿Cómo manejamos de manera óptima una condición que es difícil de diagnosticar?

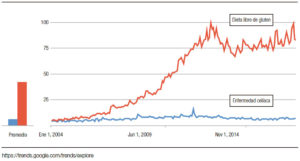

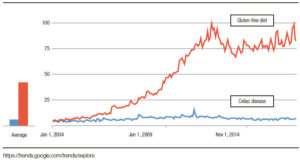

La dieta sin gluten se ha vuelto cada vez más popular en todo el mundo, y el interés general en la dieta sin gluten más allá del interés en EC ha aumentado de 2004 a 2019 (Figura 2). Esto implica que la mayoría de las personas interesadas en una dieta sin gluten no necesariamente tienen EC. No es sorprendente que haya habido un crecimiento rápido en el mercado de alimentos sin gluten debido a un número alarmante de personas que adoptan voluntariamente una dieta restringida o sin gluten.24 La única terapia disponible para el SGNC/ STNC es evitar los productos de trigo; sin embargo, se desconocen las consecuencias a largo plazo en la salud. La dieta sin gluten se ha asociado con deficiencias nutricionales que son independientes de la condición, por lo cual debería aumentar la concientización al momento de prescribir esta dieta restrictiva.24 Además, se ha demostrado que las posibles deficiencias nutricionales y la restricción del trigo afectan la riqueza y la composición de la microbiota intestinal, reduciendo los grupos bacterianos que participan activamente en la fermentación de carbohidratos, como por ejemplo, los formicutes.23, 43 Desafortunadamente, las preocupaciones descriptas no están limitadas a la restricción del gluten, y se aplicarían también a otras dietas restrictivas, como las bajas en FODMAPs. Por lo tanto, la decisión de comenzar o no una dieta restrictiva en un paciente con sospecha de SGNC/STNC es una preocupación real. Para hacer las cosas más complicadas, no todos los pacientes con SGNC/STNC responderán a una dieta restringida en trigo. Como lo sugieren tres estudios exploratorios recientes que evalúan la reacción de los síntomas a diferentes dosis de gluten en la dieta, la simple restricción de gluten/trigo en lugar de una dieta estricta sin gluten/ trigo puede ser suficiente en la población no celíaca.32, 44, 45 Si se toma la decisión de probar una dieta sin gluten/ trigo, el paso clínico más importante es descartar la EC (serología específica y endoscopía con biopsias) antes de comenzar la dieta (Tabla 2).

Figura 2. Mayor interés en el tiempo sobre dieta libre de gluten que en enfermedad celíaca.

Tabla 2. Controversias y desafíos en SGNC/STNC.

Investigaciones futuras en STNC

La definición de SGNC/STNC ha cambiado con los años y todavía no existe un consenso sobre cuál es el término más apropiado para definir la condición. No hay una presentación clínica clara, y hay más de un componente en el trigo potencialmente capaz de desencadenar una disfunción; por lo tanto, es crucial identificar cuáles son los componentes claves en el trigo, solos o en combinación, que desencadenan la reacción en esta población. Esta es la única manera para avanzar en mejores enfoques terapéuticos dirigidos a reducir selectivamente esos componentes en productos derivados del trigo. A diferencia de la EC, en la cual el contenido de gluten en los alimentos debe mantenerse por debajo de 20 ppm/día, no se ha identificado cuál es el umbral en SGNC/STNC y la reducción de la cantidad de algunas proteínas de trigo o fructanos a un nivel que sea tolerable para estos pacientes podría ser suficiente. Para poder aclarar esto, se necesitan estudios randomizados/controlados, idealmente con diseño cruzado, comparando diferentes componentes. Además de los posibles factores desencadenantes expuestos es posible que, como en el SII, haya subgrupos de personas que tengan diferentes susceptibilidades a diferentes componentes del trigo. Por lo tanto, debemos continuar buscando marcadores biológicos que puedan ayudar a identificar subgrupos de pacientes que pueden beneficiarse con alguna dieta restrictiva en particular. Las recomendaciones sobre si iniciar o no una dieta restrictiva deben basarse en la evidencia de que los beneficios superan los riesgos asociados. Además de dietas restrictivas, se han propuesto terapias adicionales como probióticos46 o enzimas derivadas de bacterias47 como potencial tratamiento adyuvante para pacientes con SGNC/STNC; sin embargo, la evidencia es escasa, lo que destaca la necesidad de investigación en esta área.

Contribución de los autores. MIPS and EFV revisaron la literatura y escribieron el manuscrito.

Declaraciones. EFV recibe un Canada Research Chair y es financiada por CIHR. MIPS recibe un Internal Career Award by the Department of Medicine, McMaster University.

Conflictos de interés. Los autores no tienen conflictos de interés para declarar.

Controversies and challenges in non-celiac gluten/wheat sensitivity

María Inés Pinto Sánchez, Elena F Verdu

Farncombe Family Digestive Health Research Institute, McMaster University. Hamilton, Canada.

Summary

Non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) has emerged as an intriguing and controversial topic in gastroenterology since the first reports over 40 years ago. The most recent definition requires a symptomatic reaction to gluten, or wheat containing food, the remission of symptoms with gluten or wheat challenge, and the exclusion of both celiac disease and wheat allergy. A definitive diagnosis of NCGS is challenging as there are no specific tests or biomarkers, and we still question the exact trigger for the condition. There have been several studies, including randomized-controlled trials (RCT), that aimed to understand whether it is gluten or the carbohydrate fraction in wheat, that trigger symptoms in non-celiac patients. Here, we review the literature to address outstanding controversies and challenges related to the diagnosis and management of this condition, as well as areas of interest for future studies.

Abbreviations

NCSG: non-celiac gluten sensitivity.

NCWS: non-celiac wheat sensitivity.

CD: celiac disease.

ATIs: amylase trypsin inhibitors.

FODMAPs: fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols.

IBS: irritable bowel syndrome.

HLA: human leukocyte antigen.

TLR: toll like receptor.

The term “non-celiac gluten sensitivity” (NCGS) was coined over 40 years ago, when Ellis and Linaker described the first case of diarrhea that improved with a gluten-free diet in the absence of celiac disease (CD).1 However, the term “gluten sensitivity” has been frequently used as an umbrella to imply celiac disease, which has generated confusion. CD is defined as an autoimmune enteropathy induced by gluten in genetically susceptible people. It has a well understood pathophysiology and a recommended diagnostic work-up. Conversely, the debate regarding the definition and pathophysiology of NCGS endures, which has been recently renamed non-celiac “wheat” sensitivity (NCWS) (Figure 1).2

Figure 1. History and advances since the first report of non-celiac gluten sensitivity.

It is important to realize the diagnosis of NCWS is performed almost entirely on the basis of clinical presentation and self-referral that gluten containing food induces symptoms. Diagnosis, therefore requires a symptomatic reaction to gluten, or wheat-containing food, in individuals in whom CD and wheat allergy has been ruled out.3 The diagnosis is therefore based on the consensus definition of the condition, requiring (1) a symptomatic reaction to gluten/wheat, (2) symptom resolution after exclusion of wheat-containing food, and (3) re-appearance of symptoms with reintroduction of gluten/wheat products.4 In the absence of validated biomarkers, a diagnosis of NCWS can only be made by a double-blind, placebo-controlled, dietary crossover challenge with gluten, which is difficult to apply in clinical practice.5 Moreover, the challenge study does not confirm that the original symptoms, prior to challenge, were indeed due to gluten, carbohydrates or other components in wheat. Of people self-reporting gluten or wheat sensitivity, only a small proportion (16%) will have reproducible symptoms after a blinded gluten challenge of gluten versus placebo in a crossover dietary trial and fulfil the current consensus criteria for a diagnosis of NCWS.5 This clearly highlights the difficulty and controversy in diagnosing and managing this condition. In this review we will focus on the most common challenges regarding NCWS, and the areas where research is needed.

Controversies

“What’s in a name?”

«A rose by any other name would smell as sweet» in William Shakespeare’s play Romeo and Juliet, implies that the names of things do not affect what they really are. The term NCGS or NCWS has generated debate since the first reports.1 The term “gluten sensitivity” implies immune reactivity to gluten, the immunogenic proteinaceous fraction in wheat that gives dough its consistency, and this has generated confusion with CD.2 Thus, in the last years, there have been several consensus meetings attempting to re-define the condition.6-8 To avoid confusion with CD, the Oslo consensus,6 encouraged the use of the term NCGS instead of gluten sensitivity alone, and described one or more of a variety of immunological, morphological, or symptomatic manifestations precipitated by the ingestion of gluten in individuals in whom CD has been excluded. As defined by Sapone et al. NCGS is a reaction to gluten in which both allergic and autoimmune mechanisms have been ruled out, suggesting that NCGS is a diagnosis of exclusion.7 The most recent consensus in Salerno, introduced a 2-step algorithm where patients should improve their symptoms in a 6 week period on gluten-free diet (GFD), followed by a second period of recurrence of symptoms after double blind placebo-controlled challenge for one week with a crossover design.3 The challenge should be performed with capsules containing 8 g of gluten, at least 0.3g of Amylase Trypsin Inhibitors (ATIs) in a Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides and Polyols (FODMAPs)-free vehicle, and a gluten-free placebo.3

In a recent review, Catassi et al. introduced the new term “gluten or wheat sensitive IBS” which includes patients who present with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)- type symptoms triggered by gluten.8 In addition to IBS symptoms, patients may present a variety of gastrointestinal and extra-intestinal symptoms. Volta et al. reported that the most frequent extra-intestinal symptom was mental confusion or a “foggy mind”, defined as a sensation of lethargy elicited by gluten, which is observed in 42% of the cases.9, 10 Other extra intestinal symptoms identified were fatigue, skin rash, headache, joint and muscle pain (fibromyalgia-like syndrome), leg or arm numbness, depression, anxiety and anemia. Therefore, the clinical diagnosis of NCWS is not straight-forward and so far the most complex diagnosis proposed by the Salerno criteria is impractical. When patients with suspected NCWS are given a blinded gluten challenge vs. placebo as suggested by the Salerno criteria, only 22% will have confirmed NCWS.11

Other tests have been used to support the diagnosis of NCWS. For instance, duodenal biopsies performed in NCWS patients shows normal villous length, with or without increased intraepithelial lymphocytes and less likely increased eosinophils.11, 12 While some have suggested immune reaction to gluten challenge, for example increased rates of basophils in biopsies of NCGS,13 others were not able to confirm these findings.14

Unlike CD, there is no specific serology to diagnose NCWS. Anti-gliadin antibodies, which are not specific for CD, and can be present in many other gastrointestinal conditions, are found in about 50% of patients with suspected NCWS.7, 9, 10 HLA-DQ2 and -DQ8 are present in 95-99% of CD patients, but carriage of these haplotypes in healthy people is common, being present in about 30- 40% of most populations.15 Some studies suggested that HLA-DQ2 and -DQ8 may be slightly more frequent in NCWS (~50%), however, this has been controverted by others.15 In a recent study, Maki et al. evaluated genetic predisposition in 50 NCWS patients compared to non- NCWS controls.16 They found that the most common genotype combinations within the gluten-sensitive cohort were A1-3/B2-6 and A1-5/B2-6, and the first was present only in NCWS population. Although the idea of identifying a genetic predisposition for this condition is exciting, it is not yet clear.

The lack of a clear clinical presentation and diagnostic tests to identify NCWS leads to difficulties in estimating properly its prevalence. In addition, the majority of patients that self-identify wheat as the responsible for their symptoms are already on a gluten-free or wheat-restricted diet by the time they consult a physician.17 In a US study involving over 7000 people from the general population, Digiacomo et al.18 identified NCWS in up to 6% of the US population, and the prevalence could be up to 13% if self-reported NCWS is considered.17

Why do we need to understand the mechanisms involved in NCWS?

It is commonly accepted that understanding the mechanisms behind symptom generation is the key to develop research conducive to a treatment or clinical management. Complex disease is difficult to manage because it is often multifactorial. The potential mechanisms involved in the pathophysiology of NCWS are many, and include, as in IBS, alterations in intestinal permeability, stimulation of innate immunity and changes in gastrointestinal motility. The main distinction between IBS and NCWS would be the trigger: While IBS has many triggers, gut dysfunction and symptom generation in NCWS, is assumed to be induced mainly by wheat consumption. As such, NCWS could be considered part of the spectrum of food-induced IBS. In terms of clinical picture, others argue that NCWS presents with a plethora of non-digestive symptoms (fatigue, etc.) that, although also present in some IBS patients, does not clinically define the syndrome, whose diagnosis relies on abdominal pain and change in bowel function.9, 10 Therefore, it could be hypothesized that specific mechanisms apply to NCWS that differ from those in general IBS.

There has been particular interest in clarifying whether intestinal permeability is altered in NCWS. An initial study by Sapone et al. found no alterations in intestinal permeability in NCWS compared with CD.19 Subsequent studies found opposite results, which may be related to differences in methodology between studies, and more importantly, variances in defining NCWS which may lead to selection bias.20-23

Immune tolerance to dietary antigens is the key to prevent undesirable responses to innocuous antigens ingested with food; therefore, loss of tolerance to gluten or other wheat proteins in NCWS could involve an immune mediated mechanism.24, 25 In vitro studies have demonstrated that digests of gliadin increase the expression of co-stimulatory molecules and the production of proinflammatory cytokines in monocytes and dendritic cells.26, 27 In addition, clinical studies have demonstrated increased expression of TLR-2 in the intestinal mucosa of non-celiac compared to celiac patients, suggesting a role of the innate immune system in the pathogenesis of non-celiac reactions to gluten or other wheat components.19 In a recent study, Gomez Castro et al. have shown that the p31-43 peptide (p31-43) from a-gliadin can induce an innate immune response in the intestine and that this may initiate pathological adaptive immunity.28 The role of this or other immunogenic peptides in NCGS/WS is not clear, and yet needs to be explored.

It is important to stress that other proteins in wheat, such as a-amylase/trypsin inhibitors (ATI) and wheat lectin agglutinin, have recently shown to induce innate immune pathways2 and has opened the field to other non-gluten trigger proteins in wheat as responsible of symptoms in non-celiac population. There is an increasing interest in the role of ATI as activators of innate immune responses in monocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells through toll like receptor (TLR) 4-MD2-CD14 complex.29 Furthermore, a recent study by Caminero et al. has shown greater immune activation in mice fed both gluten and ATI compared to those fed only gluten or only ATI, indicating a potential synergistic effect.30

In addition to protein fractions, wheat contains a group of carbohydrates, called fructans, which are members of fermentable oligosaccharide, disaccharide, mono-saccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs) that are poorly absorbed in the small intestine.2 In a placebo-controlled, cross-over rechallenge study Biesikiersky et al. suggested that gluten had no effect in patients with self-reported NCGS after dietary reduction of FODMAPs, however, this study included a mixed population of IBS patients that likely respond to a myriad of dietary exclusion diets, including placebo.31 Other methodological issues such as short wash-out periods between challenges may difficult the interpretation of results. A recent study by Skodje et al. suggested that fructans rather than gluten, induces symptoms in self-reported NCWS. The mechanisms for these reactions were not investigated in any of this studies.32

Changes in gastrointestinal motility and gut micro-biota have been proposed as potential mechanism in NCWS. Animal studies have shown that gliadin can trigger smooth muscle hyper-contractility and cholinergic nerve dysfunction in mice expressing the human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DQ8 genes, but without evident duodenal atrophy.27

Few clinical studies have investigated changes in gastrointestinal motility triggered by wheat components. Even though an initial study by Vázquez Roque21 showed that gluten-free diet had no significant effects on gastrointestinal transit in a cohort of IBS patients with diarrhea, a more recent study by our group showed that, normalization of gastrointestinal motility in IBS patients was limited to those with anti-gliadin antibodies.33

The search for trigger/s in NCWS is embroiled in polemics

One of the most controversial areas in NCWS is identifying whether gluten or other wheat protein or carbohydrate fractions trigger symptoms.

Several clinical trials (Table 1) as well as mouse studies, have attempted to address this issue with controversial findings. Gluten has been an obvious target since the condition was first described.1 Different randomized placebo controlled trials34-40 has shown that a gluten challenge triggers gastrointestinal and extra-intestinal symptoms.

The main limitation is that gluten challenge is rarely a pure challenge and as previously noted, wheat contains other immunogenic proteins29, 30 and carbohydrates,31, 32 that may contribute to symptoms in NCWS alone or through a synergic effect. However, the evidence in clinical setting is scarce.

The effect of a diet low in ATI has not yet been tested in a clinical trial, and there is only one trial evaluating the role of fructans in patients with NCWS or IBS. Finally, it remains unclear why some people who are perfectly healthy suddenly experience NCWS. Although the predisposing factors are unknown, it has been suggested that dysbiosis following a gastroenteritis may lead to the development of NCWS.41

There are different mechanisms by which microorganisms might provide direct pro-inflammatory signals to the host promoting breakdown of oral tolerance to food antigens or indirect pathways that involve the metabolism of protein antigens and other dietary components by gut microorganisms, which may explain reactions to wheat.42

Table 1. Summary of clinical trials in NCGS/NCWS (Adapted from Pinto-Sanchez et al., NMO 2018).

How do we optimally manage a condition that is difficult to diagnose?

The gluten-free diet has become increasingly popular around the world, and the overall interest in gluten-free diet has been growing from 2004 to 2019; which is beyond the interest in CD (Figure 2). This implies the majority of people interested in a gluten-free diet, may not necessarily have CD. Not surprisingly, there has been a well-known rapid market growth of gluten-free foods, due to an alarming number of individuals voluntarily adopting a gluten-free or restricted diet.24

The only available therapy for NCWS is avoidance of wheat products; however, the long-term health consequences of this are unknown. Gluten-free diet has been associated with nutritional deficiencies which are independently of the condition,24 which may raise some awareness at the time of prescribing this restrictive diet. In addition, potential nutritional deficiencies, wheat restriction has been shown to affect the richness and composition of small intestinal and fecal microbiota, reducing bacterial groups actively involved in carbohydrate fermentation such as Firmicutes.23, 43

Unfortunately, the previous concerns will also apply to other restrictive diets such as the low in FODMAPs. Therefore, deciding whether to start or not a gluten-free diet in a patient with suspected NCWS is a real concern. To complicate things further, not all patients with NCWS will respond to a wheat restricted diet. As suggested by three recent exploratory studies evaluating symptoms reaction to different doses of gluten in the diet, gluten/ wheat restriction rather than gluten/wheat free diet may be sufficient in NCWS population.32, 44, 45 If a decision to trial a gluten-free diet is taken, the most important clinical step is to rule out CD, with specific serology and endoscopy in that patient, prior to starting the restrictive diet. (Table 2).

Future research in NCWS

The definition of non-celiac gluten or wheat sensitivity has changed over the years and there is still no consensus on the most appropriate term to define the condition.

There is more than one symptom in NCWS, more than one potential component in wheat capable of triggering dysfunction, and hence the answer is likely to be complex and involve more than one trigger. However, it will be crucial to identify what the key wheat components are, alone or in combination. This is the only way we will advance in better therapeutic approaches aimed at selectively reducing those components in wheat-derived products. As opposed to CD where gluten content in food should be kept below 20 ppm/day, no such threshold has been identified in NCWS and it may be sufficient to reduce the quantity of some wheat proteins or fructans to a level that is tolerable to these patients. Adequate randomized-controlled trials with crossover design and appropriate washout period, comparing different components are strongly needed to identify this. In addition to multiple triggers, it is possible that, as in IBS, subgroups of people have different susceptibility to different wheat components.

Therefore, we should continue the search for biomarkers that may help identify subgroups of patients who may benefit from particular dietary counselling.

Recommendations on whether, or not, to start a restriction diet should be based on the evidence that benefits outweigh the associated risks. Additional therapies such as probiotics46 or bacteria derived enzymes47 have been proposed as adjuvant treatment for NCWS, however, the evidence is scarce to date, which highlights the need of research in this area.

Figure 2. There is more interest over time in the gluten free diet than in celiac disease.

Table 2. Controversies and challenges in NCGS/NCWS.

Authors contributions. MIPS and EFV reviewed the literature and wrote the manuscript.

Authors Disclosure. EFV holds a Canada Research Chair and is funded by CIHR. MIPS hold an Internal Career Award by the Dep. of Medicine, McMaster University.

Competing interests. The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

- Ellis A, Linaker BD. Non-coeliac gluten sensitivity? Lancet 1978; 1: 1358-1359.

- Volta U, Pinto-Sánchez MI, Boschetti E, Caio G, De Giorgio R, Verdu EF. Dietary triggers in irritable bowel syndrome: Is there a role for gluten? J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2016; 22: 547-557.

- Catassi C, Elli L, Bonaz B, Bouma G, Carroccio A, Castillejo G, Cellier Ch, Cristofori F, de Magistris L, Dolinsek J, Dieterich W, Francavilla R, Hadjivassiliou M, Holtmeier W, Körner U, Leffler DA, Lundin KEA, Mazzarella G, Mulder ChJ, Pellegrini N, Rostami K, Sanders D, Skodje GI, Schuppan D, Ullrich R, Volta U, Williams M, Zevallos VF, Zopf Y, Fasano A. Diagnosis of Non- Celiac Gluten Sensitivity (NCGS): The Salerno Experts’ Criteria. Nutrients 2015; 7: 4966-4977.

- Catassi C, Bai JC, Bonaz B, Bouma G, Calabrò A, Carroccio A,Castillejo G, Ciacci C, Cristofori F, Dolinsek J, Francavilla R, Elli L, Green P, Holtmeier W, Koehler P, Koletzko S, Meinhold Ch, Sanders D, Schumann M, Schuppan D, Ullrich R, Vécsei A, Volta U, Zevallos V, Sapone A, Fasano A. Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity: the new frontier of gluten related disorders. Nutrients 2013; 5: 3839-3853.

- Potter M, Walker MM, Talley NJ. Non-Celiac Gluten or Wheat Sensitivity: Emerging disease or misdiagnosis? Med J Aust 2017; 207: 211-215.

- Ludvigsson JF, Leffler DA, Bai JC, Biagi F, Fasano A, Green PH, Hadjivassiliou M, Kaukinen K, Kelly CP, Leonard JN, Lundin KE, Murray JA, Sanders DS, Walker MM, Zingone F, Ciacci C. The Oslo definitions for coeliac disease and related terms. Gut 2013; 62: 43-52.

- Sapone A, Bai JC, Ciacci C, Dolinsek J, Green PHR, Hadjivassiliou M, Kaukinen K, Rostami K, Sanders DS, Schumann M, Ullrich R, Villalta D, Volta U, Catassi C, Fasano A. Spectrum of gluten related disorders: consensus on new nomenclature and classification. BMC Med 2012; 10: 13.

- Catassi C, Bai JC, Bonaz B, Bouma G, Calabrò A, Carroccio A, Castillejo G, Ciacci C, Cristofori F, Dolinsek J, Francavilla R, Elli L, Green P, Holtmeier W, Koehler P, Koletzko S, Meinhold Ch, Sanders D, Schumann M, Schuppan D, Ullrich R, Vécsei A, Volta U, Zevallos V, Sapone A, Fasano A. Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity: the new frontier of gluten related disorders. Nutrients 2013; 5: 3839-3853.

- Volta U, Bardella MT, Calabro A, Troncone R, Corazza GR; Study Group for Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity. An Italian prospective multicenter survey in patients suspected of having Non Celiac Gluten Sensitività BMC Med 2014; 12: 85.

- Volta U, Caio G, Karunaratne TB, Alaedini A, De Giorgio R. Non- Celiac Gluten/Wheat Sensitivity: advances in knowledge and relevant questions. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017; 11: 9-18.

- Talley NJ, Walker MM. Celiac Disease and Nonceliac Gluten or Wheat Sensitivity: The risks and benefits of diagnosis. JAMA Intern Med 2017; 177: 615-616.

- Marsh M, Villanacci V, Srivastava A. Histology of gluten related disorders. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench 2015; 8: 171-177.

- Carroccio A, Mansueto P, Iacono G, Soresi M, D’Alcamo A, Cavataio F, Brusca I, Florena AM, Ambrosiano G, Seidita A, Pirrone G, Rini GB. Non-Celiac Wheat Sensitivity diagnosed by double-blind placebo-controlled challenge: exploring a new clinical entity. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107: 1898-1906.

- Bucci C, Zingone F, Russo I, Morra I, Tortora R, Pogna N, Scalia G, Iovino P, Ciacci C. Gliadin does not induce mucosal inflammation or basophil activation in patients with Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 11: 1294-1249.

- Casella G, Villanacci V, Di Bella C, Bassotti G, Bold J, Rostami K. Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity and diagnostic challenges. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench 2018; 11: 197-202.

- Maki M, Caporale D. HLA-DQ1 Alpha and Beta Genotypes Associated with Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity. The FASEB Journal 2017; 31: 612.1.

- Aziz I, Lewis N, Hadjivassiliou M, Winfield SN, Rugg N, Kelsall A, Newrick L, Sanders DS. A UK study assessing the population prevalence of self-reported gluten sensitivity and referral characteristics to secondary care. Eu J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 26: 33-39.

- Digiacomo DV, Tennyson CA, Green PH, Demmer RT. Prevalence of gluten-free diet adherence among individuals without celiac disease in the USA: results from the Continuous National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009-2010. Scand J Gastroenterol 2013; 48: 921-925.

- Sapone A, Lammers KM, Casolaro V, Cammarota M, Giuliano MT, De Rosa M, Stefanile R, Mazzarella G, Tolone C, Russo MI, Esposito P, Ferraraccio F, Cartenì M, Riegler G, de Magistris L, Fasano A. Divergence of gut permeability and mucosal immune gene expression in two gluten-associated conditions: celiac disease and gluten sensitivity. BMC Med 2011; 9: 23.

- Hollon J, Puppa EL, Greenwald B, Goldberg E, Guerrerio A, Fasano A. Effect of gliadin on permeability of intestinal biopsy explants from celiac disease patients and patients with Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity. Nutrients 2015; 7: 1565-1576.

- Vázquez-Roque MI, Camilleri M, Smyrk T, Murray JA, Marietta E, O’Neill J, Carlson P, Lamsam J, Janzow D, Eckert D, Burton D, Zinsmeister AR. A controlled trial of gluten-free diet in patients with irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea: effects on bowel frequency and intestinal function. Gastroenterology 2013; 144: 903-911.

- Bárbaro MR, Cremon C, Caio G, De Giorgio R, Volta U, Stanghellini V, Barbara G. Increased zonulin serum levels and correlation with symptoms in Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity and irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea; Proceedings of the UEG Week 2014; Vienna, Austria. 18-22 October 2014.

- Uhde M, Ajamian M, Caio G, De Giorgio R, Indart A, Green PH, Verna EC, Volta U, Alaedini A. Intestinal cell damage and systemic immune activation in individuals reporting sensitivity to wheat in the absence of coeliac disease. Gut 2016; 65: 1930-1937.

- Pinto Sánchez MI, Verdu EF. Non Celiac Gluten or Wheat Sensitivity: It’s complicated! Neurogastroenterol Motil 2018; 30: e13392.

- Carroccio, A. Searching for the immunological basis of wheat sensitivity. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016; 13: 628-630.

- Nikulina M, Habich C, Floh SB, Scott FW, Kolb H. Wheat gluten causes dendritic cell maturation and chemokine secretion. J Immunol 2004; 173: 1925-1933.

- Verdu EF, Huang X, Natividad J, Lu J, Blennerhassett PA, David CS, McKay DM, Murray JA. Gliadin-dependent neuro-muscular and epithelial secretory responses in gluten-sensitive HLA-DQ8 transgenic mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2008; 294: G217-G225.

- Gómez Castro MF, Miculán E, Herrera MG, Ruera C, Pérez F, Prieto ED, Barrera E, Pantano S, Carasi P, Chirdo FG. p31-43 Gliadin Peptide Forms Oligomers and Induces NLRP3 Inflammasome/Caspase 1- Dependent Mucosal Damage in Small Intestine Front Immunol 2019; 10: 31.

- JunkerY, Zeissig S, Kim SJ, Barisani D, Wieser H, Leffler DA, Zevallos V, Libermann TA, Dillon S, Freitag TL, Kelly CP, Schuppan D. Wheat amylase trypsin inhibitors drive intestinal inflammation via activation of toll-like receptor 4. J Exp Med 2012; 209: 2395-2408.

- Caminero A, McCarville J, Zevallos VF, Pigrau M, Yu XB, Jury J, Galipeau HJ, Clarizio AV, Casqueiro J, Murray JA, Collins SM, Alaedini A, Bercik P, Schuppan D, Verdu EF. Lactobacilli degrade wheat amylase trypsin inhibitors to reduce intestinal dysfunction induced by immunogenic wheat proteins. Gastroenterology 2019 (in press).

- Biesiekierski JR, Peters SL, Newnham ED, Rosella O, Muir JG, Gibson PR. No effects of gluten in patients with self-reported Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity after dietary reduction of fermentable, poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates. Gastroenterology 2013; 145: 320-328.

- Skodge GI, Sarna VK, Minelle IH, Rolfsen KL, Muir JG, Gibson PR, Veierød MB, Henriksen C, Lundin KEA. Fructans rather than gluten, induces symptoms in patients with self-reported Non- Celiac Gluten Sensitivity. Gastroenterology 2018; 154: 529-539.

- Pinto Sánchez MI, Nardelli A, Borejovic R, Causada Calo N, McCarville J, Samuels K, Uhde M, Suzanne Hansen S, Smecuol E, Armstrong D, Moayyedi P, Alaedini A, Collins SM, Bai JC, Verdu EF, Bercik P. Antigliadin antibodies predict the symptomatic response to gluten-free diet and improvement in gastrointestinal motility in IBS patients. Gastroenterology 2017; 152: S45.

- Biesiekierski JR, Newnham ED, Irving PM, Barrett JS, Haines M, Doecke JD, Shepherd SJ, Muir JG, Gibson PR. Gluten causes gastrointestinal symptoms in subjects without celiac disease: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106: 508-514.

- Di Sabatino A, Volta U, Salvatore C, Biancheri P, Caio G, De Giorgio R, Di Stefano M, Corazza GR. Small amounts of gluten in subjects with suspected Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Cross-Over Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 13: 1604-1612.

- Shahbazkhani B, Sadeghi A, Malekzadeh R, Khatavi F, Etemadi M, Kalantri E, Rostami-Nejad M, Rostami K. Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity has narrowed the spectrum of irritable bowel syndrome: A Double-Blind Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2015; 7: 4542-4554.

- Zanwar VG, Pawar SV, Gambhire PA et al. Symptomatic improvement with gluten restriction in irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective, randomized, double blinded placebo controlled trial. Intest Res 2016; 14: 343-350.

- Zanini B, Baschè R, Ferraresi A, Ricci C, Lanzarotto F, Marullo M, Villanacci V, Hidalgo A, Lanzini A. Randomised clinical study: gluten challenge induces symptom recurrence in only a minority of patients who meet clinical criteria for Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 42: 968-976.

- Elli L, Tomba C, Branchi F, Roncoroni L, Lombardo V, Bardella MT, Ferretti F, Conte D, Valiante F, Fini L, Forti E, Cannizzaro R, Maiero S, Londoni C, Lauri A, Fornaciari G, Lenoci N, Spagnuolo R, Basilisco G, Somalvico F, Borgatta B, Leandro G, Segato S, Barisani D, Morreale G, Buscarini E. Evidence for the presence of Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity in patients with functional gastrointestinal symptoms: results from a multicenter randomized double-blind placebo-controlled gluten challenge. Nutrients 2016; 8: 84.

- Dale HF, Hatlebakk JG, Hovdenak N, Ystad SO, Lied GA. The effect of a controlled gluten challenge in a group of patients with suspected Non-Coeliac Gluten Sensitivity: A randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled challenge. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2018 Mar 15.

- Rostami K, Rostami-Nejad M, Al Dulaimi D. Post gastroenteritis gluten intolerance. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench 2015; 8: 66-70.

- Caminero A, Meisel M, Jabri B, Verdú EF. Mechanisms by which gut microorganisms influence food sensitivities. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019; 16: 7-18.

- De Palma G, Nadal I, Collado MC, Sanz Y. Effects of a gluten-free diet on gut microbiota and immune function in healthy adult human subjects. Br J Nutr 2009; 102: 1154-1160.

- Roncoroni L, Bascuñan KA, Vecchi M, Doneda L, Bardella MT, Lombardo V, Scricciolo A, Branchi F, Elli L. Exposure to different amounts of dietary gluten in patients with Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity (NCGS): An Exploratory Study. Nutrients 2019: 11: 136.

- Haro C, Villatoro M, Vaquero L, Pastor J, Giménez MJ, Ozuna CV, Sánchez-León S, García-Molina MD, Segura V, Comino I, Sousa C, Vivas S, Landa BB, Barro F. The dietary intervention of transgenic low-gliadin wheat bread in patients with Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity (NCGS) showed no differences with Gluten Free Diet (GFD) but provides better gut microbiota profile. Nutrients 2018; 10: 1964: 1-15.

- Fosca A, Polsinelli L, Aquillo E. Effects of probiotic supplementation in Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity patients. J Hum Nutr Food Sci 2015; 3: 1073.

- Ido H, Matsubara H, Kuroda M, Takahashi A, Kojima Y, Koikeda S, Sasaki M. Combination of gluten-digesting enzymes improved symptoms of non-celiac gluten sensitivity: a randomized single-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2018; 9: 181.

- Skodje GI, Henriksen C, Salte T, Drivenes T, Toleikyte I, Lovik AM, Veierød MB, Lundin KE. Wheat challenge in self-reported gluten sensitivity: a comparison of scoring methods. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017; 52: 185-192.

Correspondencia: María Inés Pinto-Sánchez

1280 Main st west, Hamilton, ON. L8S4K1. Canadá

Tel.: +1 905 525 9140

Correo electrónico: pintosm@mcmaster.ca

Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam 2019;49(2): 166-182

Revista ACTA Órgano Oficial de SAGE

Revista ACTA Órgano Oficial de SAGE